Men have had their say. It is but fitting now that a woman should have hers, especially as the woman who assumes to speak does so with an authority man cannot venture to claim. (18)

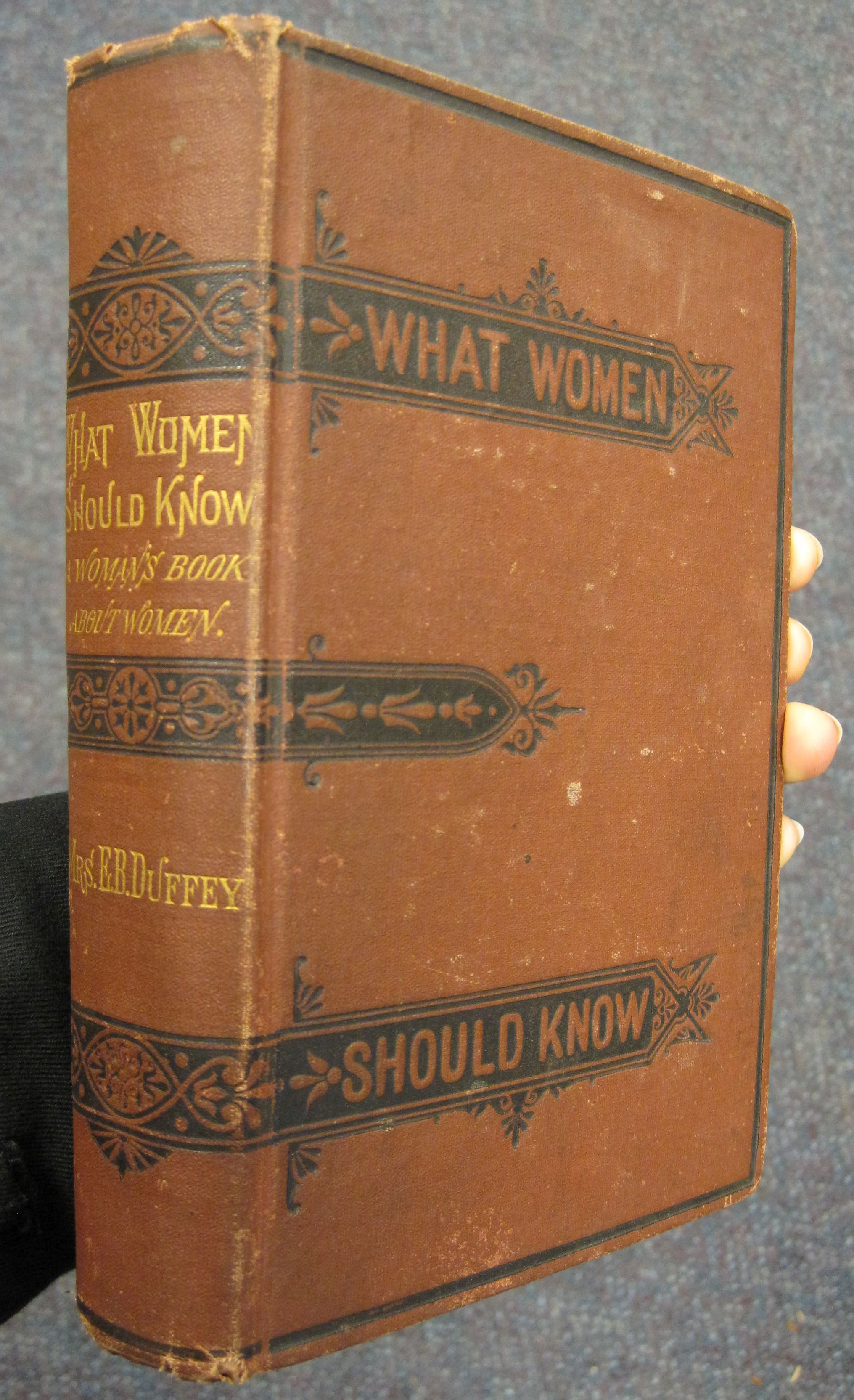

So writes Eliza Bisbee Duffey in the introduction to What Women Should Know: A Woman’s Book About Women Containing Practical Information for Wives and Mothers (1873). Part women’s health guide, part sex-ed manual, and part feminist tract, the work offers a refreshingly accurate, no-nonsense look at such topics as puberty, conception, childbirth, and motherhood, all from a much-needed woman’s perspective. In What Women Should Know, Duffey seeks to arm a “new regime” (248) of women — those “striving to do, and claiming to do, many things… heretofore… considered beyond their physical and mental capabilities” (19) — with a thorough knowledge of their bodies’ workings. This knowledge, Duffey hopes, will enable them to better safeguard their health and maximize their potential, reconciling new roles in the workplace with those of the domestic realm. Duffey’s work is, in many respects, groundbreaking: she de-stigmatizes menstruation, declaring that it “is not a disease” (44); details the physical and emotional “Evils of Stays” (41) that not only warp women’s bodies, but convince them that they are naturally flawed; broaches the taboo topic of marital rape, an issue largely unacknowledged (or thought not to exist) at the time (117); and argues that women’s seeming mental and physical shortcomings are not “inherent to the sex” (19), but the result of miseducation. Bear in mind that Duffey was writing about women’s bodies at a time when sex education was thought to be, at best, a morally dubious topic, and the confidence and clarity with which she delivers her message of empowerment seem all the more remarkable.

Surprisingly, many of Duffey’s points remain relevant in 2016 America. She appears to have been an early proponent of gender-neutral play, contending that maternal “instinct” is not innate but instilled, and that few young girls dream of becoming mothers. Boys and girls alike, when given a doll to play with, will naturally make it their “baby.” Likewise, adolescent girls are naturally as inclined to “romping” outside as their brothers. Mothers should permit them to be “tomboyish,” running, swimming, and climbing trees as they please, rather than admonishing such healthy behavior as “improper and unlady-like” and forcing them to partake in “calisthenics, gymnastics… and other feminine substitutes for exercise which so many persons recommend” (35).

Such equality between the sexes, Duffey contends, should also structure education. She argues that when boys and girls attend classes together, there are moral (as well as intellectual) benefits. She writes that “the two sexes exert a restraining and an elevating influence upon each other, and where they are mingled in educational institutions on the same terms of freedom and equality as in the home, there the standard of morality will be found to be highest” (56). (Anyone who attended high school in this century can see that this is a bit of a rosy picture, but good for Duffey for joining the co-ed movement so early on.) She also believes that the effects of co-education should extend beyond the classroom to make adult gender roles more fluid. Boys should learn housework and sewing, while girls should learn how to harness a horse and “use carpenters’ and gardeners’ tools with ease and dexterity” (161) so that they are later able to assist their spouses.

Duffey’s example of the benefits of such shared practical duties? That of the “washer-man,” a husband who (heaven forbid!) endeavored to wash five weeks’ worth of accumulated laundry in order to help his sick wife. Duffey describes how, in only three hours, the man had neatly and efficiently completed what would have taken his wife an entire exhausting day. Duffey concludes wryly, “I have felt convinced ever since that whenever a woman occupies the wash-tub she is encroaching upon man’s sphere, as he can do a washing quite as well as she, and so much more expeditiously, neatly and easily” (161).

Decades ahead of the curve, the author also challenges stigmas about working mothers. While Duffey claims that it isn’t her “purpose, in this book, to indulge in any discussion in regard to women’s right to enter into any field of labor they may see fit” (19), she makes no secret of her belief that women are capable of taking on a variety of roles outside the home while simultaneously raising healthy families. She cites several examples (including personal experience) of literary mothers who work as writers or editors and have never had to leave work for more than a month at a time to give birth and convalesce. None of these women, Duffey argues, have neglected their homes or their families in favor of work, and their infants have grown into healthy, happy, intelligent, self-sufficient young people. Again drawing from personal experience, Duffey recounts how, returning to work four weeks after giving birth to her daughter, she was met by exclamations of, “‘But your poor babe!’” Duffey’s rebuttal? That her “‘poor babe’ was the best, the quietest, the healthiest babe ever borne into the world” and that “as a child she is now bright and active beyond her years” (251).

The author maintains that not only can mothers work outside the home without negative implications for their children, but they can also excel at their jobs. In fact, Duffey believes that women can exceed male colleagues in workplace performance. A female doctor, for example, “is to be preferred to a man,” for she is “just as capable, more reliable, more sympathizing, and more helpful” (201) – especially during childbirth.

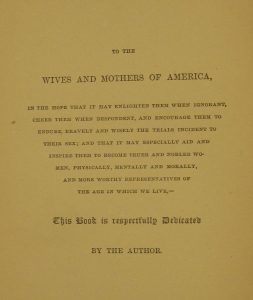

Who would have thought that modern women could find such a powerful defense of sexual equality and work-life balance in a book published in 1873? Yet over a century ago, poised on the brink of major social change for women, Duffey and her fellow nineteenth-century pioneers were already paving the way for modern motherhood, and the book’s dedication statement – made out to “the wives and mothers of America” that it may “cheer them when despondent… encourage them to endure bravely and wisely the trials incident to their sex; and… inspire them to become truer and nobler women” (5) – still rings true today.

The enduring relevance of What Women Should Know more than a century after its publication is, at least in part, a measure of our own sluggish progress toward promoting gender equality from early childhood and adopting widespread policies – such as paid parental leave – that support work-life balance. Yet this book also serves as a testament to the boldness and tenacity of Duffey and women like her, who not only challenged assumptions of their mental and physical limitations on paper, but, through their actions, proved them to be irrelevant. In this sense, the book is a celebration: it recognizes the women who began the slow process of reshaping “motherhood,” relegating it from the single purpose of a woman’s existence to just one part of her multifaceted identity — and, arguably, producing better-rounded and more fulfilled mothers along the way.

by

by