Welcome to “Students in the Stacks,” a new series of posts in which students working in Special Collections write about the finds they just can’t keep to themselves. The first post in this series is by Claire Peterson, a freshman double-major in Spanish and English in the College of Arts and Sciences and a student assistant to Rare Books Librarian Jennifer Lowe.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

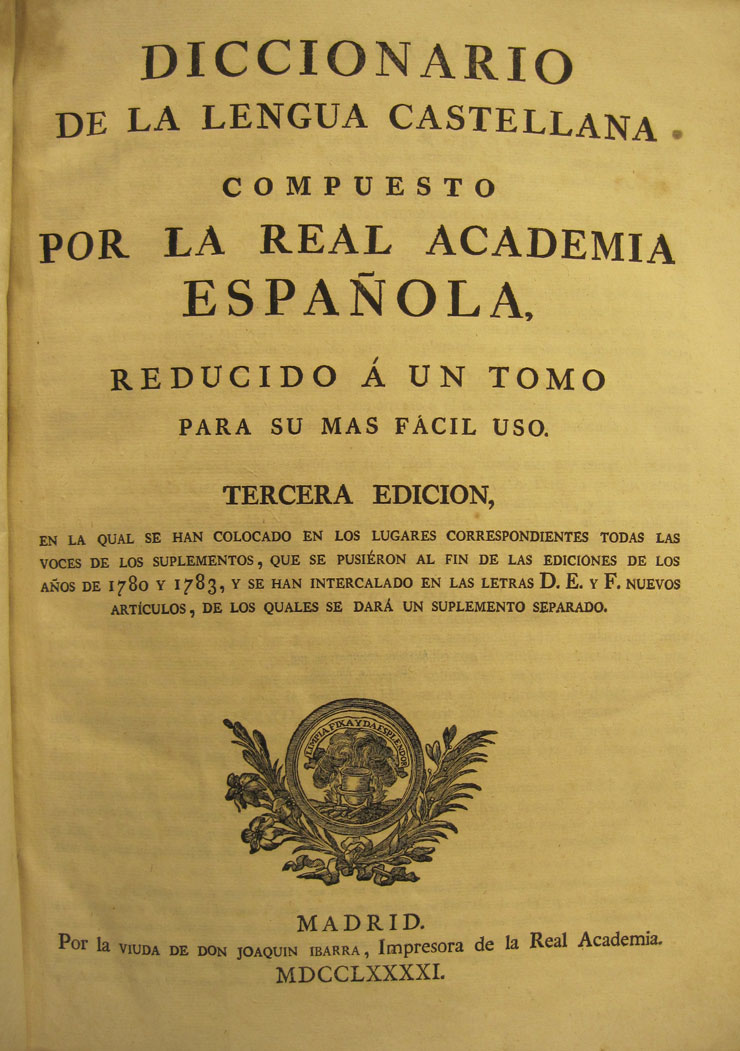

The first books to capture my attention were early versions of texts familiar to any language student, a dictionary and a grammar. Two volumes in particular, Diccionario de la lengua castellana (1791) and Gramática de la lengua castellana (1796), interested me not only because they were both published by the Real Academia Español, an organization regarded as the authority on the Spanish language, but also because they are 200-year-old precursors of the reference books I use on a daily basis.

As antiquarian books, they look very different from my modern textbooks. They are bound in leather with gold-tooled spines and marbled endpapers, printed on handmade laid paper, and were produced at the end of the hand press period in the late 18th century, before industrialization changed bookmaking. A little research revealed that the Gramática is bound in “marbled calf,” and the Diccionario in “tree calf,” both patterns created by the application of acid on the leather. Books bound in marbled calf have random swirling patterns, and tree calf bindings have patterns resembling a tree trunk and branches.

My examination of the texts themselves revealed some surprising features. In the grammar, I found a remarkable degree of similarity between this work from 1796 and my own Spanish textbooks. Although the orthography of the language has changed considerably, the minimal adjustments made to Spanish grammar make the Gramática useful still in teaching the rules of the language. The grammar’s paradigms and methods of explanation, complete with a student’s absentminded scribblings, look very familiar two centuries later.

The first thing to do when opening a dictionary is to look up a favorite word–in my case, entrelazado (interlaced, interwoven). Finding it almost halfway through the Diccionario on page 379, I was intrigued by the fact that the first six letters of the alphabet comprised more than half of the 867-page work. Nothing in the binding or the pagination suggested the book was incomplete. I found the explanation of the lopsidedness in the dictionary’s introduction. Since the last edition, only the entries through the letter “F” had been corrected and augmented, making them much longer than the latter entries, and categorizing the RAE‘s Diccionario as a work in progress.

In order to find out more about the publisher, I consulted some histories of the Spanish language in the general collection. Marking Spain as the last major European nation to establish an academy to oversee its language, the Real Academia Española (RAE) began in 1713 as a group of poets and writers who came together to discuss their literary work. Modeled after and heavily influenced by its French predecessor the Académie française, the RAE is an institution that has been considered the definitive authority on the Spanish language since its beginning. As its motto limpia, fija y da esplendor (“clean, set, and give splendor”) suggests, it sought to standardize the language of the time. Its first publication in 1726 was the Diccionario de autoridades, a dictionary of words collected from and citing passages of Spanish literary works. Eventually it became clear that the seven-thousand-odd pages of entries were perceived by the public as cumbersome and inaccessible, so in the first edition of the Diccionario de la lengua castellana (1780), excerpts from hundreds of Spanish authors were removed.

But the noble-sounding motto limpia, fija y da esplendor could have more sinister implications. The dedication of the RAE’s Gramática strikes notes of unification and glorification: “All nations should hold highly their native language, but even more so those who, while embracing a grand number of individuals, enjoy a common language, one that unites them in friendship and interest.” This sentiment addressed to Charles IV, King of Spain and dedicatee of the work, coincides with the policy to make Spanish the official language of the administration and to eliminate the use of native languages in the colonies. On April 16th, 1770, Charles III published a document entitled Real Cédula para que se destierren los diferentes idiomas que se usan en estos dominios, y solo se hable el castellano (“Official document so that different languages that are used in these territories might be banished and only Spanish be spoken”), promulgating his order that Spanish be the dominant language used in Spain and the colonies.

The Jesuits also play a role in this story. In the mid-18th century, in an attempt to significantly reduce the power of the noblemen, the monarchy made an example of the Jesuits. The Crown outlawed the work of the order and pulled out thousands of missionaries because it feared their growing power throughout the colonies. They were replaced with priests who, because of the quick exchange, were told to preach in Spanish since they had not spent years assimilating the native languages of the people as the Jesuits had.

While the joint efforts of the monarchy and the Real Academia Española to standardize the language did succeed, the long-term effects of their work to eliminate other dialects, especially those of the indigenous people of the colonies, are called into question. Persisting throughout the Hispanic-American revolutions of the early 19th century, these policies provide a sharp contrast to the ideals expressed in the dedication of the grammar, making the Diccionario and Gramática quiet witnesses to the evolutions and revolutions of language.

by

by