Were pickled oysters missing from your Thanksgiving spread? Was your turkey in need of matrimony sauce? Perhaps your guests craved suet pudding and superior bread?

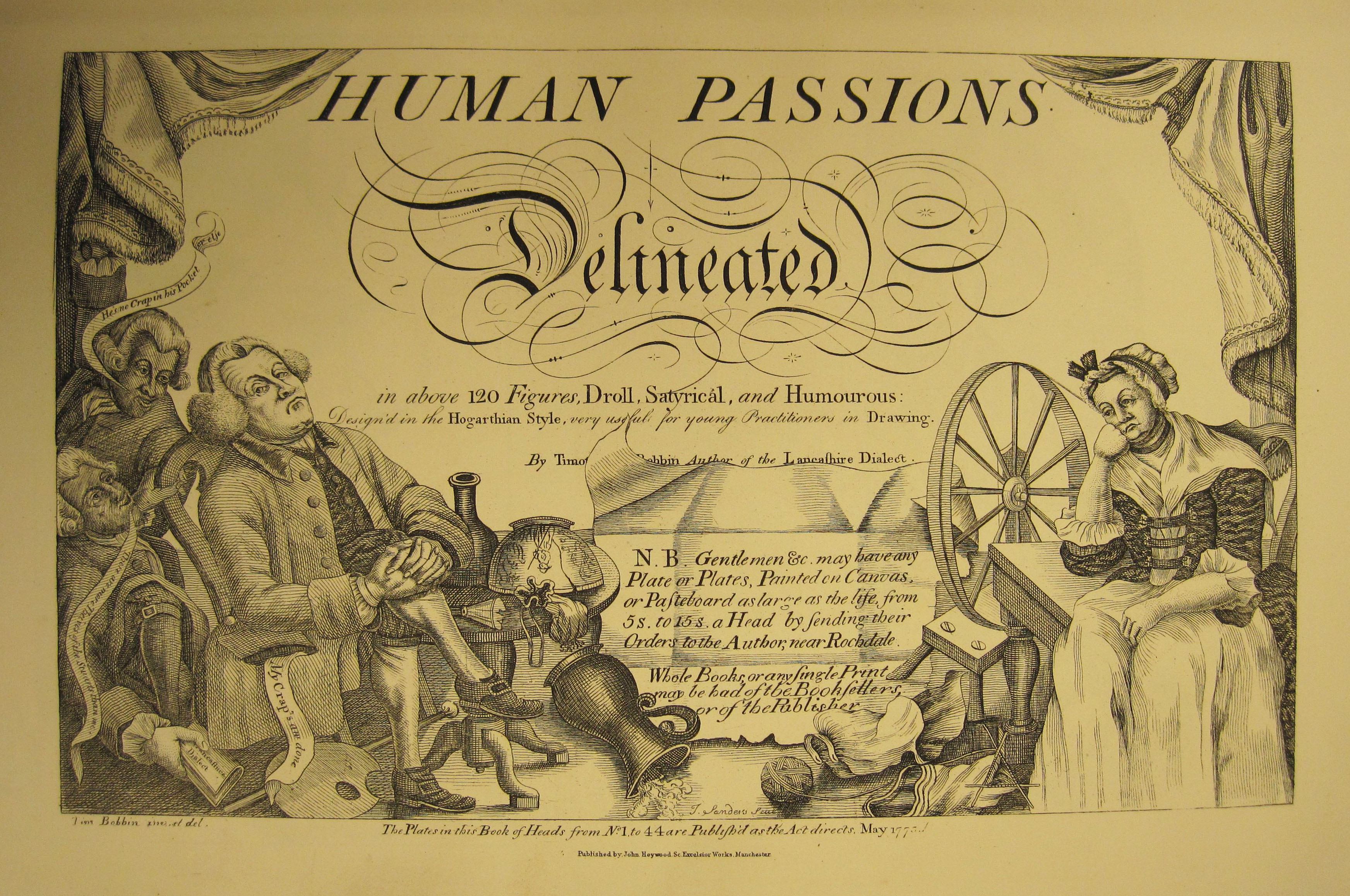

If any of these dishes tempt, disgust, or intrigue you, it’s time to consult our 1878 edition of The Home Cook Book: Compiled from Recipes Contributed by Ladies of Toronto and Other Cities and Towns. This is a book that far surpasses our modern concept of a cookbook as a collection of recipes. Instead, it might best be described as a domestic manual divided into three main parts: an etiquette book, an interlude of didactic tales, and the “meat” (and vegetables, sauces and desserts) of the book: the recipes.

The first four chapters are devoted to rules of etiquette in entertaining, and contain useful tips for the (presumably middle- or upper-class) nineteenth-century housewife. For instance, every good party hostess should have “some novelty at hand” to prevent “a very stupid half hour” (26). This novel interest could be anything from a “personage” to a “pretty girl” (clearly not the same), or simply “the latest spice of news to tell” (26). Crank up the gossip machines!

Also included are instructions for decorating one’s table for a party (let it be known that “artificial contrivances, like… tin gutters lined with moss and filled with flowers for the edges of a table… are banished by the latest and best taste” [28]) and controlling the speed at which you eat (“quiet celerity” is preferable to “majestic deliberation” [29]). Interestingly, this section contains advice for both women and men, though instruction for gentlemen is mostly limited to propriety in their behavior to ladies (and thus, their behavior within the home sphere).

Before we reach any actual recipes (this is a cookbook, isn’t it?), there comes an odd little interlude of two didactic tales. In the first part of the book, housekeeping is presented not so much as a skill that a woman acquires through hard work and industry, but as “one of those things to be imbibed without effort in girlhood” (10). The first tale, titled “The Little Housekeepers,” demonstrates the “imbibing” process by detailing the work of two young girls left to left to clean and cook while their maid is away and “Little Mother” (or so the doctor calls her – a reminder, if you needed one, that this is 1878) has sprained her ankle. Annie and Jennie dance about their tasks, clearing the table; washing the dishes (“no disagreeable work, you may be sure” [38]); tidying the bedrooms, including their brother John’s (I mention this because, as one who was also a little girl with a brother Jon, I cannot imagine a more horrifying prospect); and making lunch. The whole affair is a joyous romp, as you would expect a day’s worth of drudgery by two youngsters accustomed to leaving work to adults would be, interspersed with bouts of “kissing and petting mamma” (38). There is a marked simplification of the language used as we move from the introductory chapters to this story, and we can only hope that this child-friendly turn is for the benefit of any “little housekeepers” who might be reading the tale, and not their “Little Mothers.”

When the maid frees Annie and Jennie from their labors, we are left with Susan, the capable Mrs. Patmore of a second didactic tale. Susan paints a rosy picture of the kitchen as the “pleasantest room in the house” (43), cozily outfitted with paintings and plants, newspapers, and a window to let in fresh air and birdsong. Her romantic narrative is paired with a practical run-down of how the ideal kitchen ought to be equipped. From table to coffee pot, all of the “Necessary Utensils” of a working kitchen are listed in the style of a probate record (sans monetary values).

Having set the scene, detailing all the tools and comforts that the kitchen ought to have, the authors at last come to the recipes themselves. You’ll find, on your initial perusal, that these 137-year-old recipes are surprisingly familiar to the modern palate. Many contain ingredients – butter, sugar, a variety of meats and vegetables – standard to the twenty-first-century kitchen. Differences in how familiar dishes were prepared, however, give us a glimpse not only of how middle- and upper-class Canadian families ate in the late nineteenth century, but also of what foods they considered essential to a healthy diet. Four entire chapters are devoted to the preparation of animal proteins (fish, shellfish, poultry and game, and meats), and butter is a near ubiquitous ingredient rather than a culinary villain. (Another domestic manual of the time, The American Woman’s Home [1869] by Catherine Beecher and Harriet Beecher Stowe, lists butter among the primary food groups, and details how rancid butter has the power to ruin an entire meal. The message: butter was in everything.) Eggs pop up in surprising places, such as in a recipe for hot chocolate which calls for “the yolks of eggs well beaten” (343). Presumably, as the eggs are stirred in rather than used as a makeshift strainer as they sometimes were for coffee grounds, the yolks add a layer of richness to an already thicker drink than that to which we are accustomed today.

Other “sore thumbs” to the modern eye are the three chapters devoted to pickling, two chapters on puddings and their requisite sauces, and a multitude of recipes starring foodstuffs usually discarded today (such as suet). Unsurprisingly, nineteenth-century cooks were more apt to use all available ingredients (including fats) at their disposal, and needed ways to extend the shelf-life of perishable ingredients. They also seemed to favor cooked over raw food, even in the case of fresh vegetables. “Salad” recipes feature lightly pickled produce, fish, hard-boiled eggs, and cooked vegetables served cold.

Throughout the book, vagueness in measuring ingredients and naming dishes gives recipes both a charming and a foreign air. How many modern cookbooks would direct readers to use such inexact measurements as “a tea cup of salt” (135) or “butter size of hen’s egg” (66)? Names of many dishes are likewise inexact. Recipes such as Ada King’s “Cheap and Good Cake” and Mrs. J.D. King’s “Lovely Sponge Cake” may make me nostalgic for the dense, raisiny brown-bread of my mother’s that I dubbed “Gorgeous Bread” as a child, but they certainly don’t give me a clear picture of the recipe’s end-product.

Even more fascinating is that some recipes are not, by modern standards, recipes at all. The last two chapters, titled “Miscellaneous” and “Sick Room and Medicinal Receipts,” are an almost comically bewildering jumble of directions for making toiletries, home cleaning products, and remedies for both common and serious health complaints. Here we find instructions for everything from cleaning carpets and mixing cold cream to treating hydrophobia (“the bite of a mad dog”). A cholera remedy and a “Fig Paste for Constipation” (371) occupy a single page, and a “Remedy for Smallpox” follows “How to Get Rid of Flies” (374). No attention is paid to logically grouping recipes, and the resulting order appears to have been determined purely by how recipes fit together on the page.

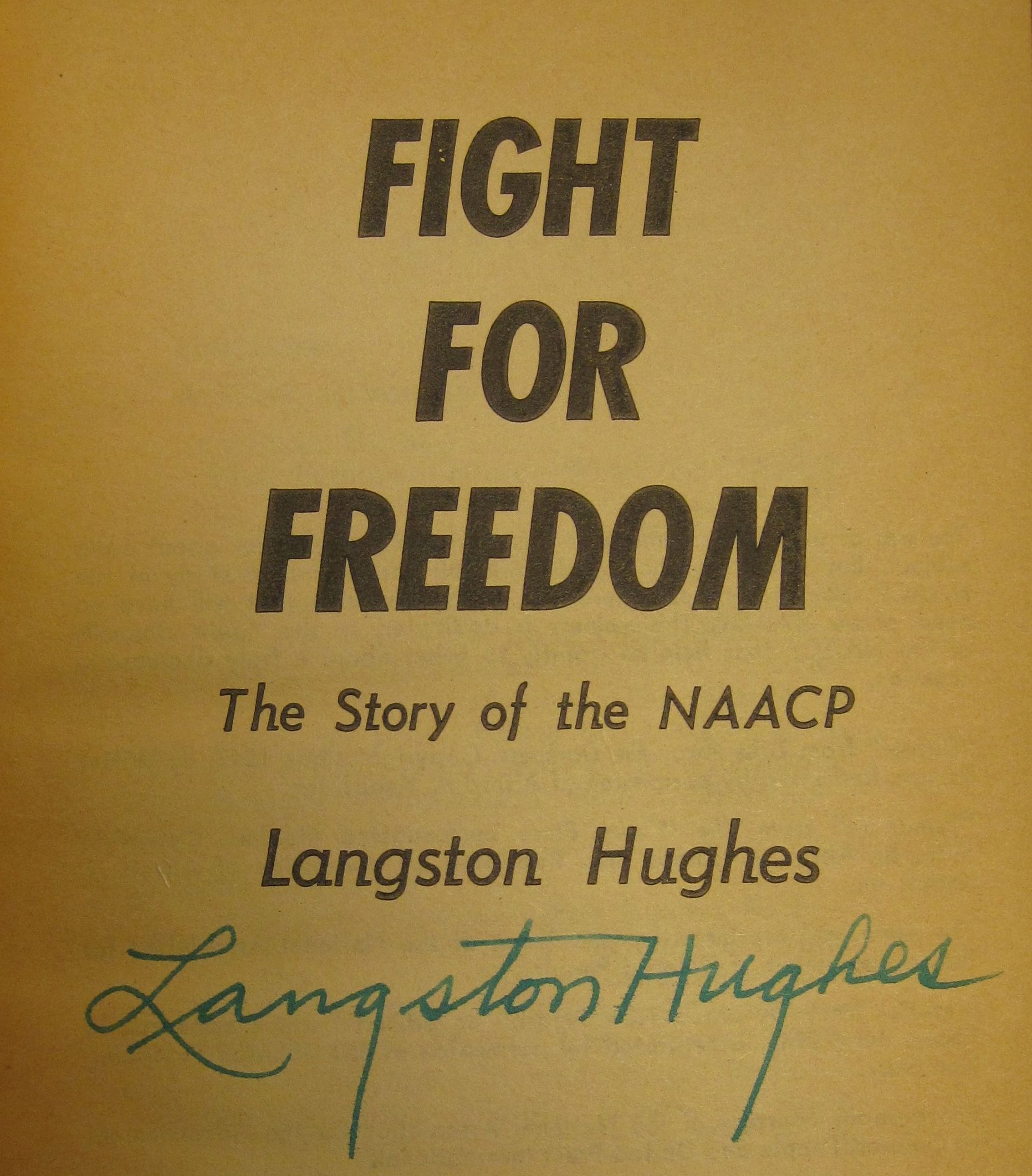

At this point you may be wondering, what are we to make of this odd little book? Despite its quirks of organization, The Home Cook Book gives us a valuable snapshot not only of the late-nineteenth-century North American diet and the culture of entertaining that surrounded it, but also of women’s roles at the time. In the domestic realm, women were the authorities, and – as evidenced by The Home Cook Book, compiled and sold by Toronto women for the benefit of a children’s hospital – the genre of domestic manuals was one in which women had a voice and could exercise it to promote social change outside the home. Compilation cook books were a venue for sharing information locally, but also must have been empowering to the housewives who saw their names in print. Most recipes are attributed to a specific contributor, whose name appears beneath the name of her dish. Some women even elevated their names to the recipe’s title, as with “Sally Munder’s Way of Dressing Cold Meat” (93). How thrilling must it have been to a woman who took the traditional path, dedicating herself to her home and family, to briefly take on the role of authoress?

It seems particularly appropriate that individual women were credited for their contributions to a cookbook, for these acknowledgements of “authorship” recognize how women and families individualize(d) recipes in their own kitchens. Food is integral to cultural, familial, and individual identity, and is powerfully evocative of memory (just see the Missouri History Museum’s books full of visitors’ coffee memories in Coffee: The World in Your Cup & St. Louis in Your Cup – it’s remarkable how a single drink conjures memories of home, holidays, and loved ones for so many people from around the world). You can see how Mrs. Savage’s recipe, “My Mother’s Favourite Pickles,” preserves not only cucumbers, but her memories of cooking with her mother. Many of the book’s dishes – presumably their contributors’ best – are likely family recipes, handed down with their charmingly vague-but-appreciative names and the inexact measurements of cooks who learned them not by reading, but by example. For some of these women, this may have been the first time their recipe was written down, which would, to them, have amounted to preserving a family treasure.

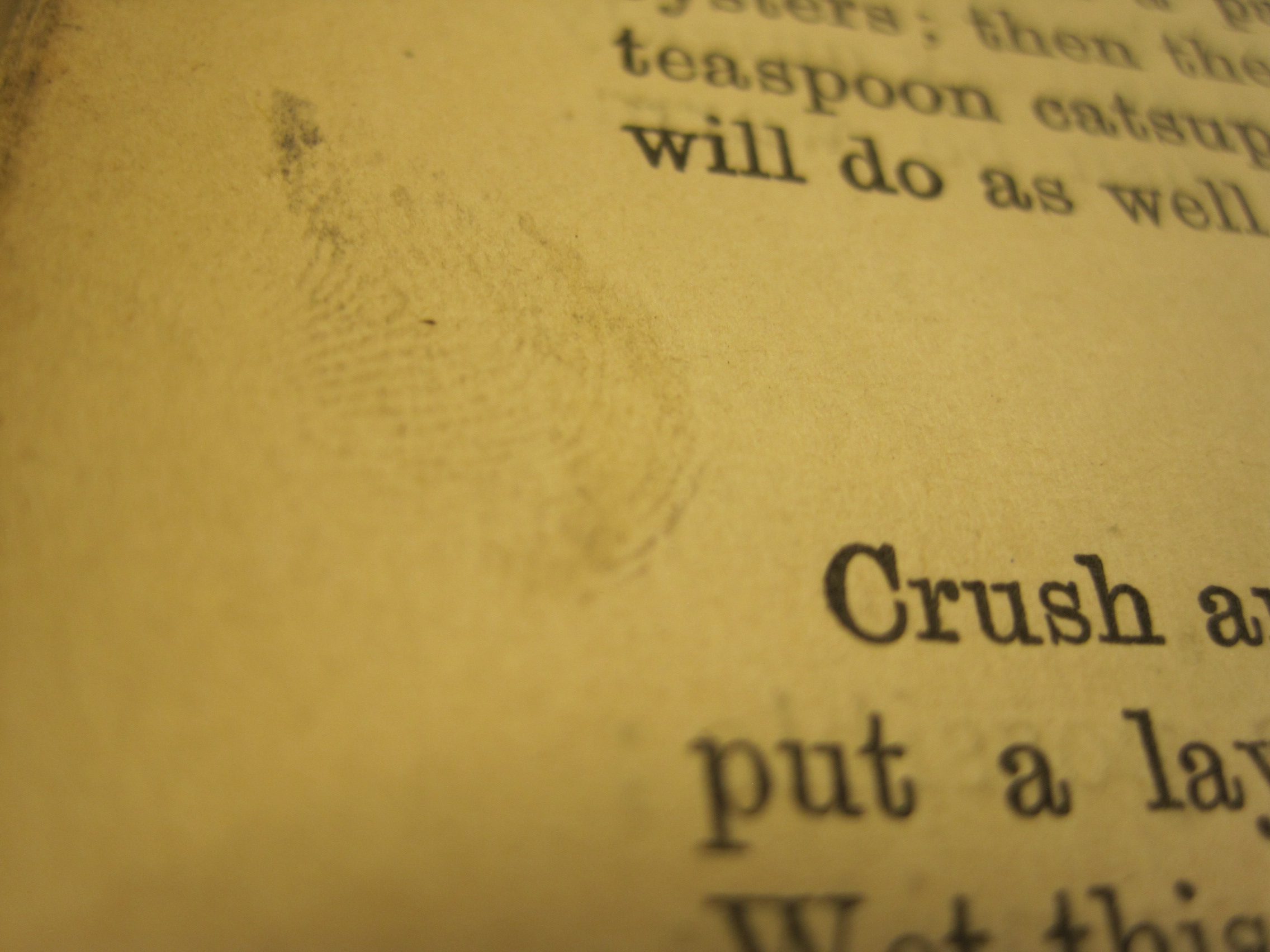

These family recipes, personal and beloved to the women who submitted them for publication, picked up another layer of women’s history when they were appropriated by those who purchased the book. Cook books arguably bear the marks of use more than any other genre, and this copy of The Home Cook Book has been spattered, stained, and so often flipped through with messy fingers that it is practically falling apart. As heavily used technical manuals, cookbooks such as this one occupy a unique place in book history, bearing testament to the wear and tear of life in a busy kitchen.

Though The Home Cook Book opens with a letter from a man addressed to its male publishers, the book is, both intellectually and physically, a women’s artifact. The opening chapters emphasize cookery and housekeeping as instinctual activities, to be simultaneously lauded as women’s “profession” and discredited as simplistic, requiring only a short book to supply “the place of the Academy” (v). Yet this short book belies any assumption that women’s roles were free of sweat and striving. Every woman’s name, printed proudly above her recipe, and every stain upon the page is an artifact of effort.

by

by

My late father was an antiques collector and gave me a copy of this book. Printed in 1878, it looks identical the images in this article…stains and all. I have yet to really peruse the pages because of its delicate condition afraid I’m going to damage it. Thank you for this article outlining the contents, I am even more fascinated now…perhaps I will risk a gentle peek through its pages. Books, after all, were written to be read. 😀