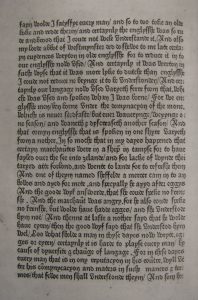

The fractured state of fifteenth-century English is colorfully expressed by printer William Caxton in the preface to his 1490 translation of Virgil’s Aeneid. To illustrate the effects of the “dyuersite [&] chauge of langage” in his time, Caxton recounts a confused communication between a southern woman and a northern merchant:

“In my dayes happened that certayn marchau[n]tes were in a ship in tamyse [the Thames] for to haue sayled ouer the see into zelande [in Holland]/ and for lacke of wynde thei taryed atte forlond [in Kent]. and wente to lande for to refreshe them[.] And one of theym named sheffelde a mercer cam in to an hows [house] and axed [asked] for mete [food], and specyally he axyed after eggys[.] And the good wyf answerde, that she coude speke no frenshe. And the marchau[n]t was angry, for he also coude speke no frenshe, but wolde haue hadde egges/ and she understode hym not/ And thenne at laste a nother sayd that he wolde haue eyren/ then the good wyf sayd that she understood hym wel/ Loo what sholde a man in thyse dayes now wryte, egges or eyren, certainly it is harde to playse euery man, by cause of dyuersite [&] chau[n]ge of langage.”

Caxton’s oft-referenced “egges” versus “eyren” anecdote may be humorous, but at its heart is a real quandary: how was Caxton to make foreign-language (and Old or Middle English) works accessible to the masses by translating them into modern English when there was more than one “English” from which to choose?

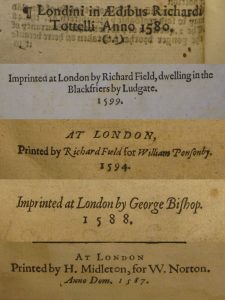

Complaints of the mutual incomprehensibility of neighboring English dialects predate Caxton, but the problems posed by a lack of language standardization were magnified in his time by the printing press. Texts were churned out at a previously unimaginable rate, and, in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, as books became more affordable, the literate population grew, publishers’ markets expanded, and national sentiment increased, more and more books were published not in Latin, but in European vernaculars. In England, where the native tongue had both Germanic and Norse roots that appeared in varying degrees in regional dialects (e.g., the Old English “eyren” and Old Norse “egges”), this meant that authors and printers of texts in the vernacular had to decide which dialect to use in order the reach the widest audience. Many (Caxton included) published in the East Midlands dialect spoken in the greater London area, and, as the word forms of this dialect were preserved in print, it increasingly became the English standard.

This “standard” of language was loose, for even within a given dialect, spelling was phonetic and notoriously mercurial. (Recall, for example, how a certain playwright might choose to go by “Shakesper” or “Shake-speare” as the mood struck him.) It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that the standardization of word forms, meaning, grammar, and usage were fully worked out and put into print.

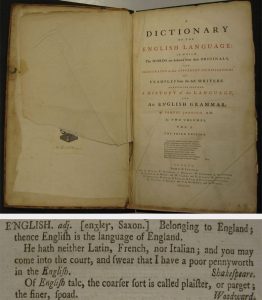

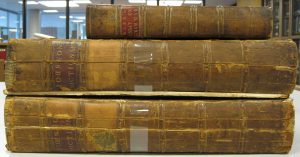

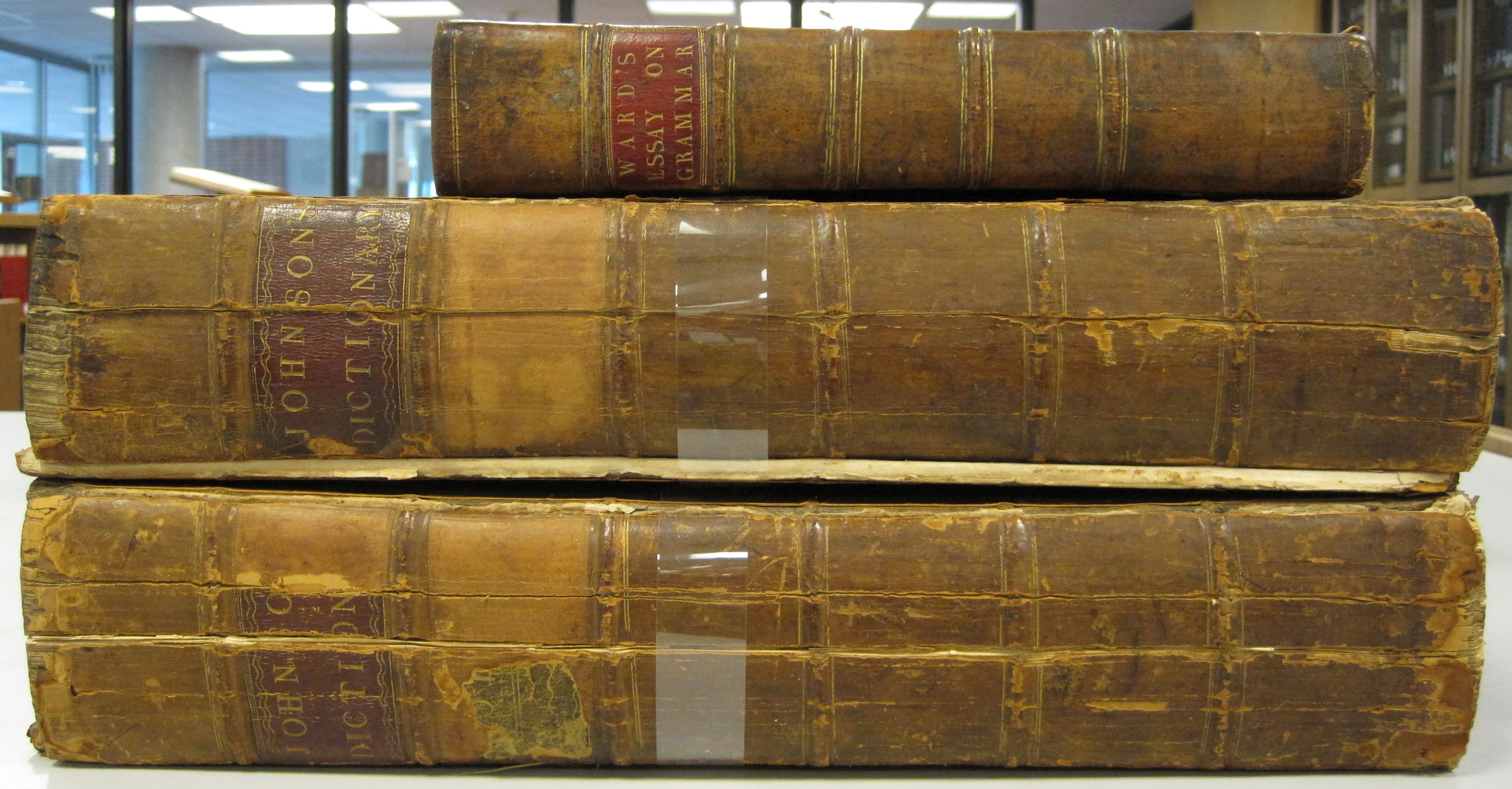

Enter: one of SLU Rare Books’ English language stars, Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language of 1755.

Johnson’s was not the first English dictionary (English scholars had been compiling “hard word” dictionaries listing long words, technical terms, and/or slang as early as 1604), but it was the most comprehensive general dictionary at the time. This is a fact that Johnson is keen to point out in his introduction, where he emphasizes the arduousness of lexicography in a language suffering from a “deficiency of dictionaries” (6). His words were not harvested from preexisting lists, but had to be “sought by fortuitous and unguided excursions into books, and gleaned … in the boundless chase of a living speech” (6) — a beautiful image of lexical scholarship.

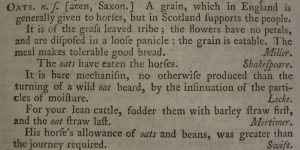

Johnson’s work is all the more impressive for its many examples of usage, mined from publications; his prefatory essay on the history of English, which traces the language’s evolution from Old English, through its Middle and Early Modern forms, and finally to Modern (eighteenth-century) English; his essay on English grammar, which laid the groundwork for grammarians such as William Ward; and the astounding speed with which the work was produced. While a comparable work in French had taken 55 years and 40 scholars to produce, Johnson was able to complete the first edition of his dictionary in only eight years and with the help of six contributors. The dictionary is overwhelmingly the work of a single man, and has been both celebrated and criticized for its evident infusion of Johnson’s personality (and biases) in the centuries since its publication.

While some of Johnson’s definitions fall short of the standard of objectivity that modern lexicographers strive for, and though some words that he painstakingly collected have since shifted in meaning or fallen out of use altogether, what I find most remarkable about his dictionary is how overwhelmingly familiar it seems to the modern reader. In organization and intent, in its colloquial style and the clarity of its definitions, and in its commitment to describing the movements of a living language rather than prescribing rules to corral it, A Dictionary of the English Language is everything that we expect a dictionary to be, for modern dictionaries have followed in its wake. Though English continues to evolve (in June 2016, over 1,000 words were formally welcomed into our lexicon by the Oxford English Dictionary), it’s worth remembering that our ability to communicate effectively across dialects was exponentially improved by standards set by eighteenth-century lexicographers and the reference tools that they created. So here’s to Johnson’s “boundless chase” — and, perhaps more importantly, to the sweet simplicity of “egg.”

____

Further reading:

For a general overview of the evolution of the English language from Anglo-Saxon Britain to today, see the British Library’s “English Timeline”: http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/evolvingenglish/accessvers/index.html

For a look at the evolution of the English dictionary into the collection of general words, definitions, and etymologies that we’re familiar with today, see “The first dictionaries of English” by John Simpson, Chief Editor of the Oxford English Dictionary: http://public.oed.com/aspects-of-english/english-in-time/the-first-dictionaries-of-english/

by

by