The guest lecture by Thomas Allen and panel discussion on the Saint Louis Exorcism of 1949 has prompted us to explore the rare book collection for older works on this subject. Although we have only two books on exorcism per se, we decided to broaden the scope of our investigation to include demons, witchcraft, and magic in the early modern period. “We” includes BEN HALLIBURTON, graduate student in History and summer assistant for Rare Books in Special Collections, and it is he who has compiled and written up this selection from our holdings and who is the author of this guest blog post.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

Exorcism is an ancient rite with various applications. Priests in the medieval Church possessed power over the supernatural and they, as well as saints, were able to drive out demons from both objects and people. Judaism, Islam, Hinduism, and other religions also have their own forms of exorcism for driving out demons and evil spirits. The Protestant Reformation and the Counter-Reformation of the sixteenth century gave occasion to re-examine many aspects of Catholic theology and practice, exorcism among them. As the Malleus malificarum of the fifteenth century was an attempt to establish a thorough and systematic definition of witchcraft in the fifteenth century, so in the sixteenth there was an effort to define possession and exorcism.

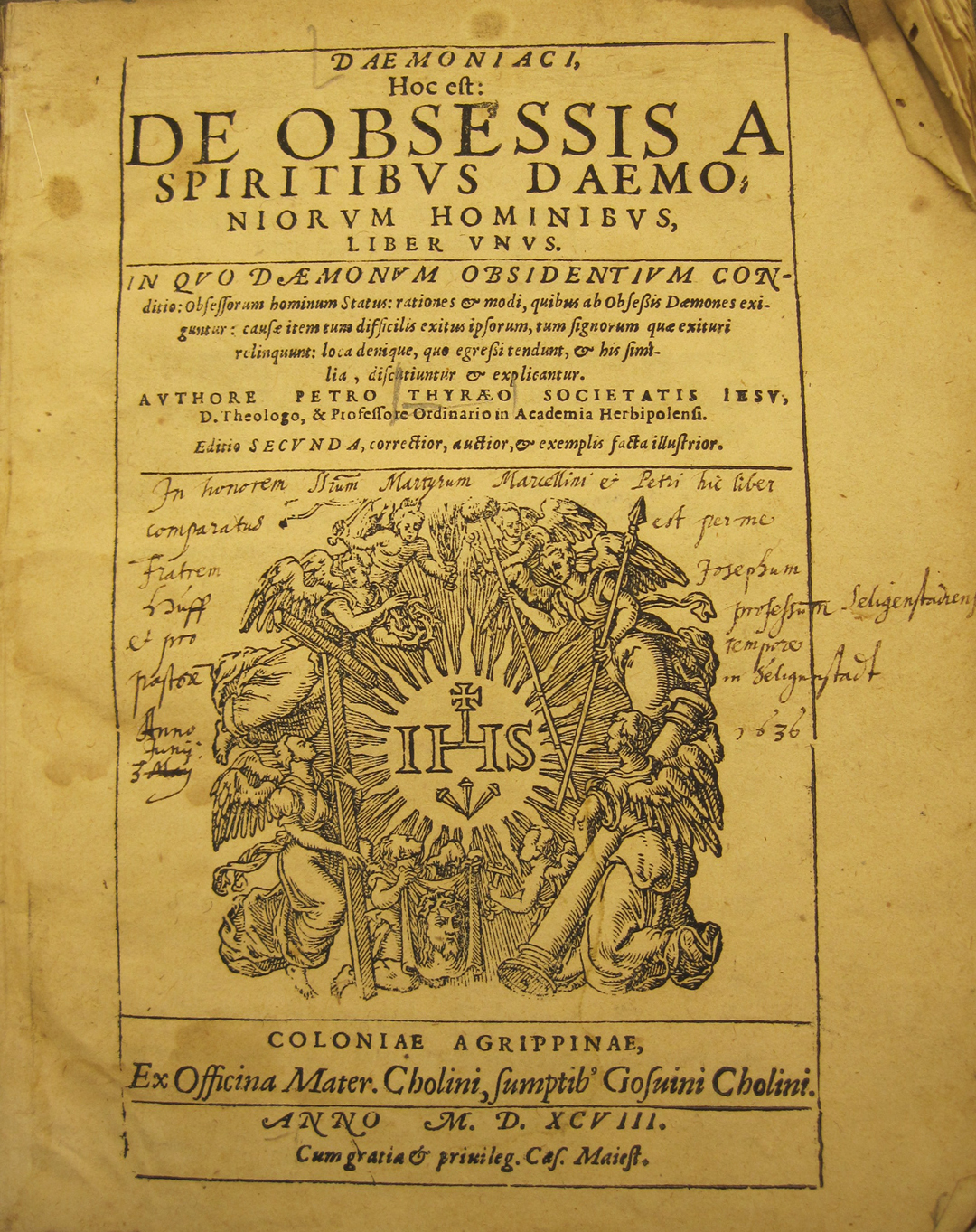

The Daemoniaci by German Jesuit Peter Thyraeus is a fascinating example of these early efforts. Appearing in 1598, it is said to be the first systematic attempt to define demonic possession and exorcism. Thyraeus lists a variety of demonic symptoms, like speaking in unknown languages and hungering for raw meat, but spends just as much time talking about what aren’t symptoms: leading an immoral lifestyle, having an unpleasant temperament, sleeping during the day, etc. His stated goal in writing the Daemoniaci was to make sure that people received proper treatment for whatever ailed them. Those suffering from what he calls a demonic “obsession” ought to receive exorcism, but those suffering from any number of other spiritual or physical problems ought to seek care elsewhere. For Thyraeus, the latter still meant seeing a priest, as he considered doctors to be quacks.

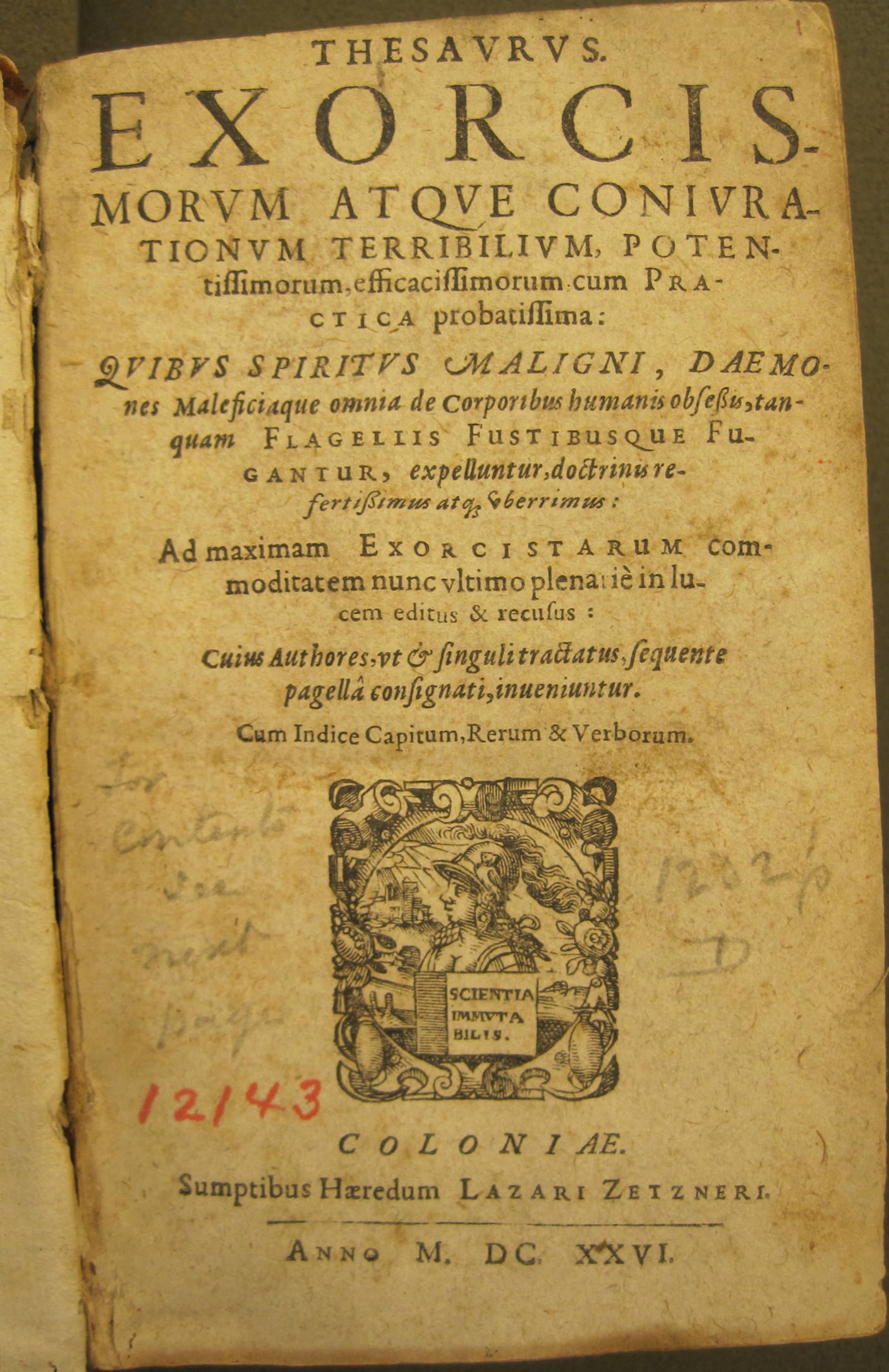

But Thyraeus did not put everyone’s doubts to rest about exorcism. Several contemporary scholars used the arguments of Aristotle and Averroes to deny the existence of any supernatural force in the natural world other than God. They were roundly dismissed as over-skeptical, but they inspired another round of collection and codification on the subject of exorcism. The most famous result is the Thesaurus exorcismorum, first printed in 1608.

The Thesaurus isn’t really one book with one author; it is a compilation of several Italian treatises on exorcism. Within its 1,272 pages are found the Flagellum daemonum and the Fustus daemonum by Girolamo Menghi, the Practica exorcistarum and the Dispersio daemonum by Valerio Polidori, the Complementum artae exorcisticae by Zacharia Visconti, and the Fuga satanae by Pietro Antonio Scampa. Though these works are all by different authors and don’t always agree, together they present a new and unified vision of exorcism. A century before, the Malleus maleficarum had suggested a combination of physical and legal remedies for cases of demonic possession, but the authors of the Thesaurus now recommended exorcism as the sole solution to any contact with the Devil or his minions.

Along these lines, the most famous of the Thesaurus’s contributors, the Franciscan exorcist Girolamo Menghi, devised a hierarchy of evil spirits from merely wicked to truly terrible. For the most part, they aligned with the classical elements: the group of demons called the Leliureon comes from fire, the Aerea from air, the Acquatile or Marino from water, the Terreo and Sotteranei from earth. These different kinds of demons worked together to tempt people to different kinds of sin, sometimes even possessing a person to weaken his resistance. An exorcist had to engage the demon, which lived inside the host like a second personality, in a sort of dialogue in order to befuddle it, terrify it, and drive it out.

Let us pause to consider two depictions of demons. The popular understanding of demons and their ways was influenced by the writings of St. Teresa of Ávila, a Catholic saint from Spain who had worked through the sixteenth century to reform the Carmelite order of monks and nuns. She had been called to the religious life by a series of ecstatic visions, which some people at the time thought were the work of the Devil rather than God.

In her autobiography, St. Teresa’s temptations and anxieties take the form of little black imps whose horns prick the sinful; she famously recommends holy water to combat them. In this engraving from a 1752 edition of her works, one of them is being trod underfoot alongside a serpent, as the saint receives a revelation from God.

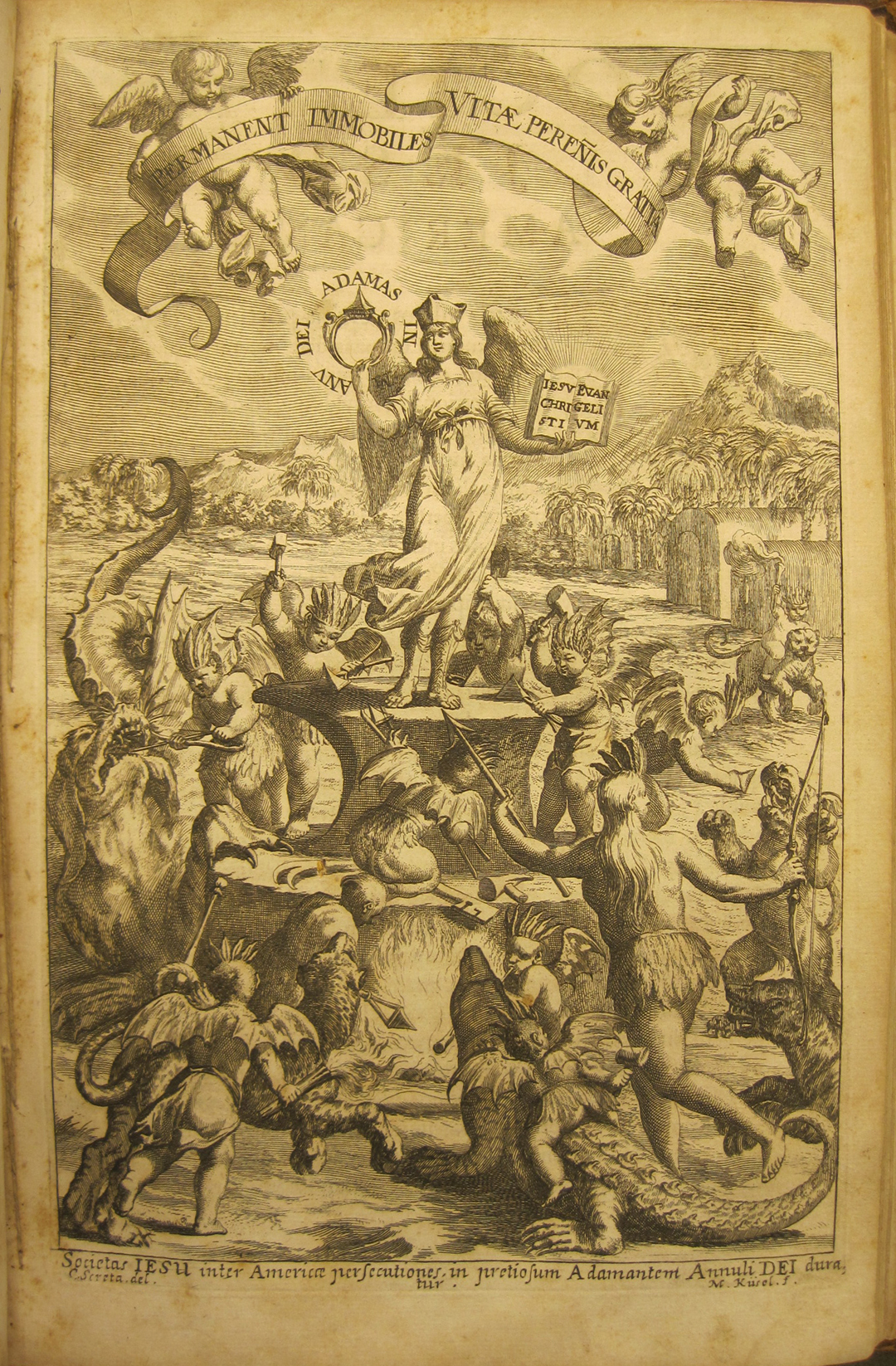

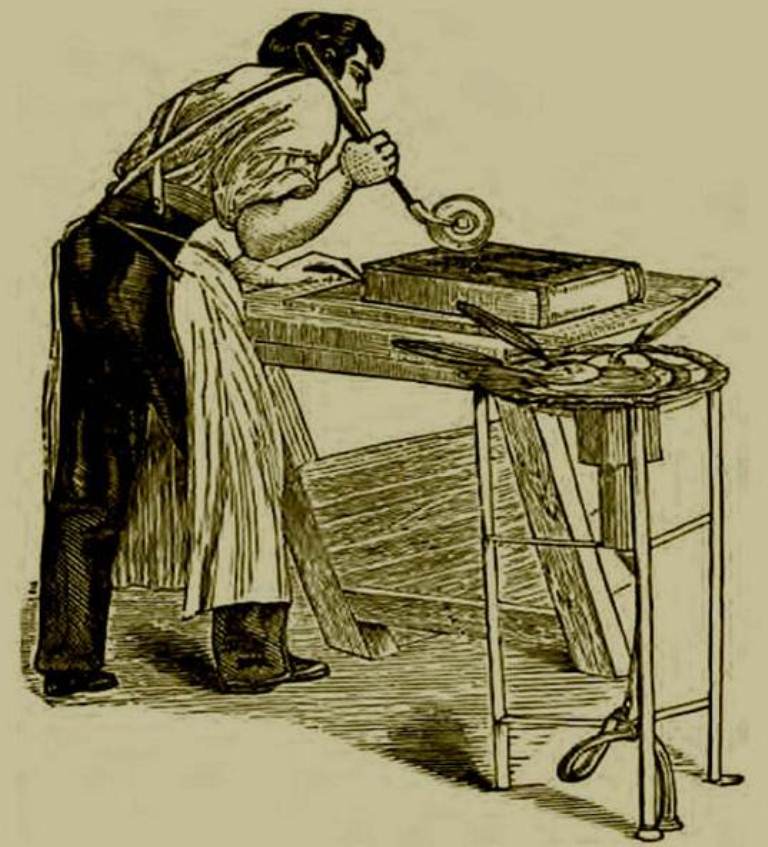

Demons were a common motif in artwork by the time of the Reformation. This history of Jesuit martyrdom organized geographically includes a baroque engraving representing the Jesuit mission in the Americas. Here we see bat-winged imps in native headdress making mischief amid the native human and animal population, forging their weapons upon an anvil where the figure of Christianity stands beleaguered but triumphant, holding a diamond ring in one hand and the Gospel in the other. This illustration is typical of the early modern worldview in which, one way or another, everything in the natural world is influenced by supernatural forces.

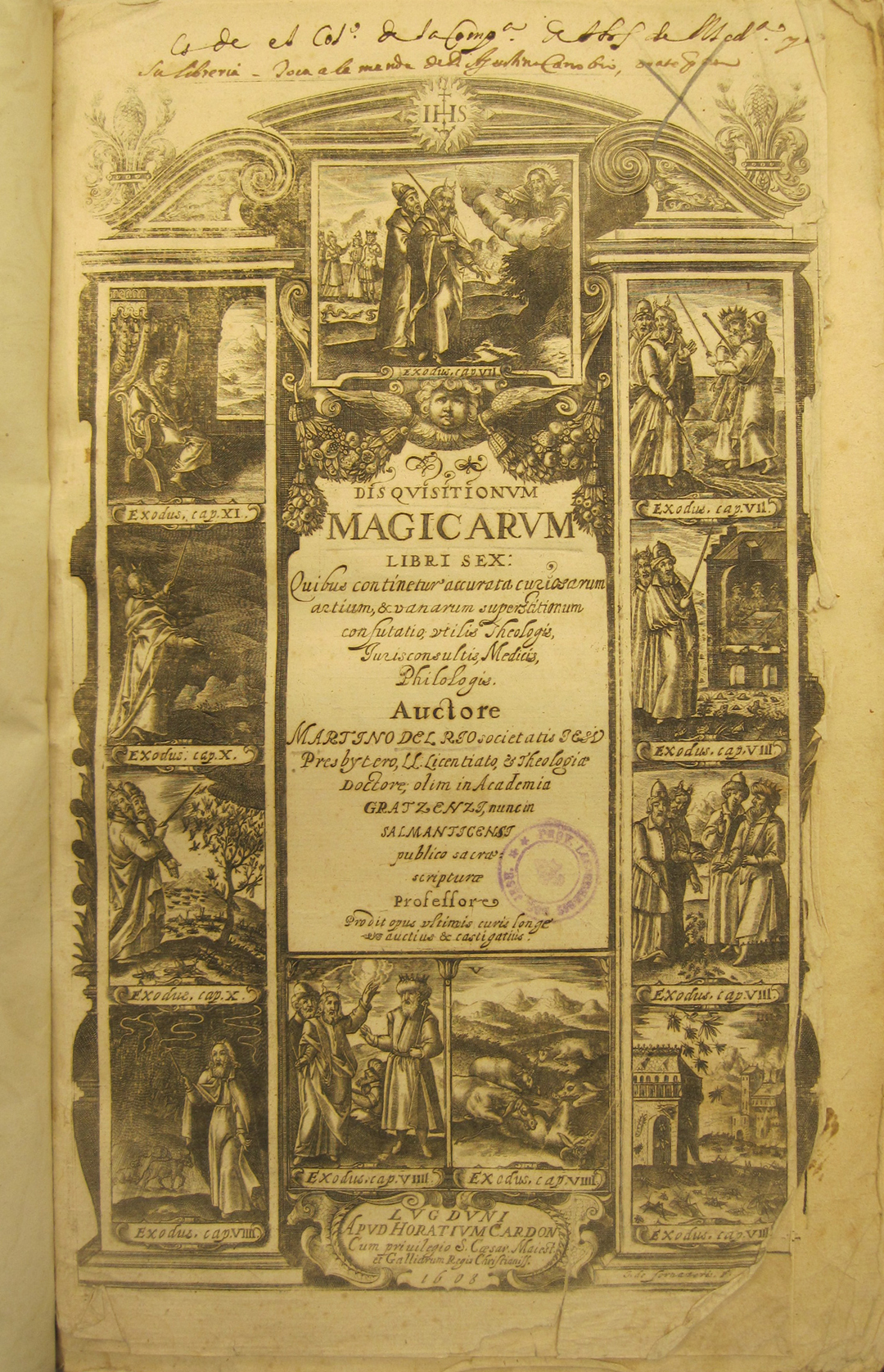

First published in 1599–1600 and reprinted at least 20 times, the Disquisitionum magicarum by Martín del Rio, a Spanish Jesuit from the Netherlands, was, like the Daemoniaci and the Thesaurus exorcismorum, part of a larger movement in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to study and understand the world in both its natural and supernatural aspects.

Though mostly about magic, del Rio’s work covers a lot of ground over the course of six books. His first four examine different magical practices to determine which ones have a demonic taint. The last two are full of advice for judges and confessors when dealing with practitioners of magic, whom del Rio argues should be treated as heretics. In his opinion, magic comes from the Devil, so to practice magic is to treat the Devil as God’s equal. Anyone who does so is therefore guilty of Manicheaism and Catharism, two of Christendom’s greatest heresies.

Del Rio’s views on magic don’t apply to miracles from God. While magic only bends the laws of nature, miracles surpass them, which is what makes God greater than the Devil. One of Del Rio’s best examples is the Ten Plagues of Egypt. Moses performed these miracles to impress the Pharaoh into letting the Jews leave Egypt. Moses is shown here with horns, due to a mistranslation in the Vulgate Bible of the Hebrew word keren as “horned.” The Pharaoh’s own sorcerers stand by and watch helplessly, their devilish magic unable to stop Moses’s godly miracles.

The distinction between magic and miracle replaced the older one from the Middle Ages between “white” and “black” magic. Whereas it used to be okay for a particularly pious person, like a priest, to cast a spell or two with good intentions, all magic came to be seen as heretical and evil after the writings of authors like del Rio became popular.

The clear response to this distinction was the persecution of witches, who were now much easier to identify. The beginning of the sixteenth century saw a drastic increase in witchcraft and witch-hunts. At the forefront were people like Nicholas Rémy, a French magistrate born in 1530.

Rémy had a grudge against witches. A beggar woman had cursed him after he refused to give her any money. When his son died in an accident, Rémy set himself on a crusade. By his own account, he gave the death sentence to 900 people, each of whom he firmly believed was guilty of witchcraft. In 1595, he compiled 10 years of witch-hunting experience in his book the Demonolatreiae, which would serve as a kind of how-to manual for others.

Throughout the early modern period, witch-hunts were one of the ways that a society could regulate its membership; most often, people on the fringes, like the homeless or the insane, were the targets of accusations.

Everyone knows about the best example of witch-hunting run amok, the Salem witch trials of 1692-93. On the testimony of four young girls, thought to be acting out their families’ feuds within the community, as many as 37 people were killed. The victims ranged from a black slave to a well-respected grandmother. Massachusetts authorities soon moved to intervene, but the mass hysteria had already taken its toll.

Many people looked for someone to blame, among them a Boston merchant named Robert Calef. He wrote a book called Wonders of the Invisible World Displayed, which denounced the famed and respected Reverend Cotton Mather for encouraging the witch-hunt with his own writings and with others, like del Rio’s Disquisitionum magicarum, discussed above. The influence of the Mather family in Massachusetts was so great that Calef had to send the book to London to be printed, but it has come to be considered one of the best sources for the Salem trials today.

For all of their notoriety, the Salem witch trials came at the end of the witch-hunting craze. The Scientific Revolution of the eighteenth century was coming, with its focus on rational and empirical thought. Reliance on the old medieval ordeals of trial by water or fire were discredited, and under attack from doctors, scientists, and philosophers belief in magic or supernatural forces as explanations for phenomena similarly waned. However, it has not vanished entirely: the exorcism 64 years ago by SLU Jesuits of a boy who seemed to exhibit demonic possession, and the fascination exerted by that case in the years since, show us that some of the oldest and most curious parts of our history survive to the present day.

by

by