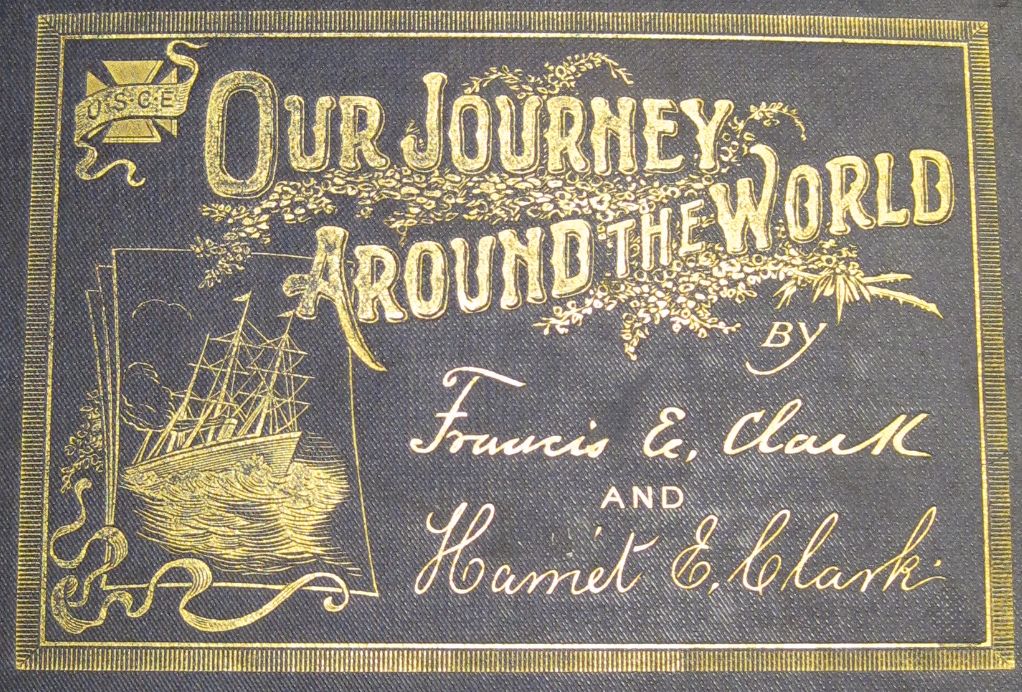

In Our Journey Around the World: An Illustrated Record of a Year’s Travel of Forty Thousand Miles Through India, China, Japan, Australia, New Zealand, Egypt, Palestine, Greece, Turkey, Italy, France, Spain, etc. (1895), American minister Francis E. Clark, founder of the nineteenth-century Christian Endeavor movement, documents his family’s year-long tour of missions throughout the world. For me, Clark’s book – from its purportedly secular content to its distinctive late-nineteenth-century binding – represents a journey from one curiosity to another.

First, there is the author’s claim that his travelogue is “distinctly a book of travel” (viii), and, beyond the preface, will not discuss the primary purpose of his family’s journey: to nurture the movement from which the youth ministry traditions of many modern evangelical Christian groups were born. As his family’s route was plotted between the homes of fellow “Endeavorers” and the bulk of their time was spent touring missions, attending prayer meetings, and speaking at conventions around the world, isolating those rare moments of leisure between religious engagements and restricting an account of the journey to those respites seems a formidable task. Unsurprisingly, the finished book could not be called entirely secular. Evidence of the Clarks’ religious beliefs and motivations is everywhere apparent, from the “USCE” flag depicted on the book’s spine to Clark’s characterization of himself, his wife, and his thirteen-year-old son as “the Pilgrim,” “Mrs. Pilgrim,” and “the Young Pilgrim” (39). The Society for Christian Endeavor, launched in 1881 as a youth group in the Portland, Maine parish where Francis Clark served as a Congregational minister, is the ever-present, seldom named character underlying his account, for, by the time Clark’s family took their world journey in 1892, it had exploded into an influential, international society, the running of which had become Clark’s new vocation. Even the title page of Our Journey Around the World makes it clear that the society has become integral to Clark’s identity, for he is named as “Rev. Francis E. Clark, D.D. President of the United Society for Christian Endeavor.”

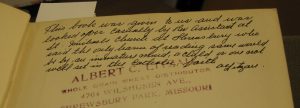

SLU’s copy carries its own unique reminder that, though the work was marketed as a secular narrative, it still promotes the author’s evangelical agenda. An annotation on the dedication page reveals that not all Christians were on board with Clark’s inter-denominational youth movement.

Clearly, the Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor was not Catholic priest-approved (at least, not in St. Michael’s Church in Shrewsbury, Missouri), and though this book could be enjoyed harmlessly by adults firmly grounded in the Catholic faith, it certainly could not be trusted in the hands of the young impressionables Clark preached to.

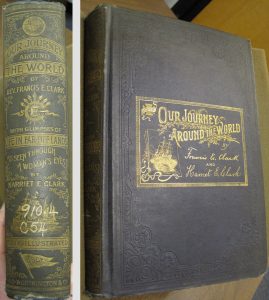

Beyond its association with a late-nineteenth-century religious movement, Clark’s book offers a fascinating glimpse into its time of publication. Our copy’s gold-stamped blue cloth binding models a typical late-nineteenth-century cover design, and its bric-a-brac spine decoration – in the midst of which are a finely delineated ship, a globe, and an embellished “CE,” for “Christian Endeavor” – gives a clear visual summary of the book’s contents to prospective readers. (This is only the first example of the book’s fondness for self-summary, which also manifests in descriptive, dramatic, and sometimes hilarious running titles — see the image below for some representative examples.)

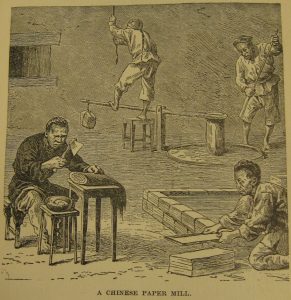

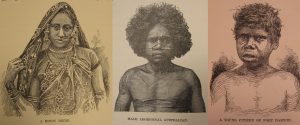

The volume is also filled with illustrations, and its title page proudly boasts that it is “superbly illustrated with steel-plate portraits, and upwards of two hundred choice engravings.” Today, we take for granted that our travel guides will be filled to the brim with high-quality, color photographs, but in 1897, an abundance of realistic illustrations in an affordable travel book was still novel. The excitement underlying the claim that these illustrations are “from special photographs taken from life expressly for this work” (xiii) is nearly tangible, and the persistence with which they were advertised implies that these reproduced photographs considerably boosted the book’s marketability.

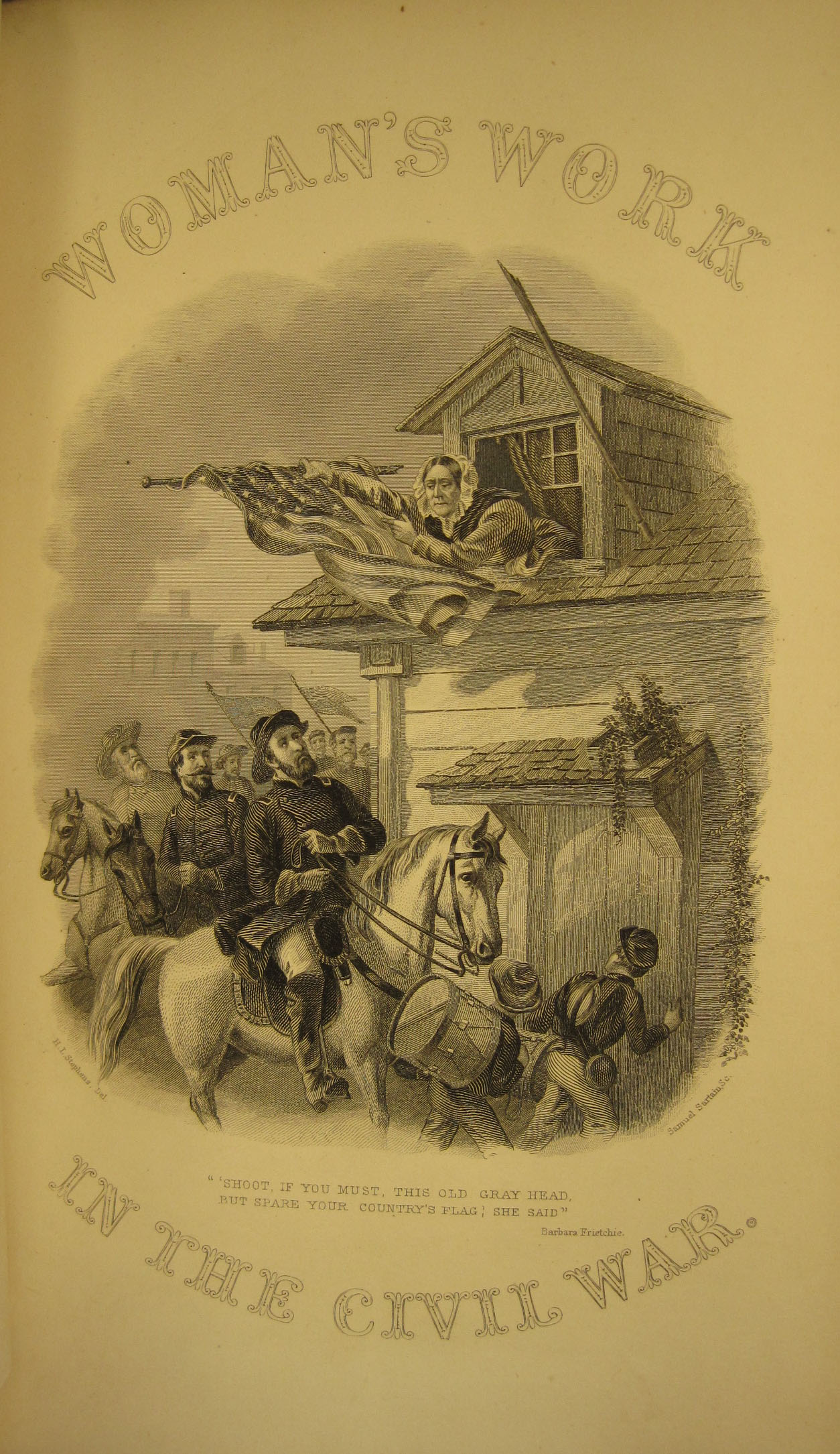

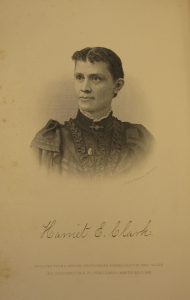

While Our Journey Around the World is certainly worthy of attention as a physical artifact, it was the content of its last 46 pages that initially caught my eye. Clark hands this final section of the 641-page tome over to his wife, Harriet E. Clark, who ends the book with Glimpses of Life in a Far-Off Land, As Seen Through a Woman’s Eyes. Admittedly, the balance of authority is somewhat skewed to our modern eyes (how gracious to cede your wife a whole seven percent of your work), it’s important to remember that Clark needn’t have shared authorship with his spouse at all. That Harriet Clark’s voice made it into the volume indicates that her husband valued her as an (almost) equal partner, and hints at the crucial role she played in his work. In fact, Mrs. Clark stood beside (or, at least, slightly behind) her husband from the very first meeting of the Society of Christian Endeavor, and was instrumental in driving up female participation in their flagship youth group. She was a founding member who shared in her husband’s travels, raised their son in accordance with his teachings, and, within the society, was fondly known as “Mother Endeavor.”

In Glimpses of Life in a Far-Off Land, Harriet Clark brings to travel the same maternal perspective she was known for bringing to her husband’s work, observing domestic life through a whirlwind of women’s prayer meetings, teas, and tiffins (an Anglo-Indian term for luncheon or tea, as well as my new favorite word). While her husband attempts to describe everything from a country’s flora and fauna (e.g., the wallaby with its “puny little forelegs which seem so utterly inadequate to the occasion” (106)) to its cultural traditions, Harriet Clark hones in on women’s clothing, education, daily life, and rules of etiquette. She also turns her shrewd housewife’s eye on the realities of nomadic life, addressing those “weary housekeepers” (597) back home with delightfully unexpected bouts of dry humor. In one tongue-in-cheek passage addressing American women bored with running households, she casts the monotony of traveling for days on an unchanging seascape as the greatest adventure. She writes:

If you do not like your front yard to-day, you can console yourself with the thought that it will be your back-yard tomorrow. If you are not pleased with the Banda Sea this week, you know you will have the Sulu Sea next week. If Thursday Island does not suit you, wait a day or two and you can have Friday Island, or Saturday Island.

It is true that all water looks very much alike, whether it is the Yellow Sea or the Bosphorus, but then you can always assure yourself that it is not the same, and that you are looking out upon a different place from yesterday. (599)

While Our Journey Around the World is full of entertaining anecdotes and observations, it also has a darker side. The Western authors’ hubris and belief in the superiority of their own culture, paired with the desire to “improve” other peoples, permeates the text. From the patronizing tone of Francis Clark’s introduction, which thanks missionary friends for taking his family “into the homes of the natives” and showing them their “oddities,” we can infer that, of all the people the Clarks met in their travels abroad, it was only the American and European missionaries that they viewed as equals. Thus, while Clark’s descriptions of the “natives” occasionally begin with admiration, they generally end in culturally insensitive, back-handed compliments. In one passage, Clark acknowledges that paper, gunpowder, movable type, and the compass were all invented in China (refreshing admissions!), only to assert that the entire nation is an example of “arrested development,” and that “as she [China] made these articles a thousand years ago she makes them now” (264). Even worse is Clark’s frequently racist language, which he slips into the narrative with the oblivious insensitivity of his time, but which is jarring to modern readers. Matters aren’t helped by the book’s much-touted illustrations, which, while “taken from life,” exoticize rather than humanize the people they depict.

Harriet Clark’s narrative is, if anything, even more cringe-worthy, for her observations of the women and children of other nations are laden with the sentiment of the white man’s burden. Take, for example, her description of the children of Port Darwin, Australia, in which she laments that “little is being done to civilize or Christianize these people,” continuing, “My heart went out to those poor, dirty, black babies, and I wished with all my heart that I could do something for them” (605). Never does she consider that the people she and her husband encounter in their travels may not want – or need – to be “helped” through westernization. Instead, she fixates on the (perceived) positive impact that her missionary friends have had on communities around the world. In one instance, she notes that the average Japanese maiden is “very pretty,” but she wishes that she would “learn to walk more gracefully instead of shuffling along in an awkward manner in… clumsy wooden shoes” (606); in another, she notes that mission-educated Japanese girls are very refined, and “would compare favorably with the girls at Wellesley or Smith or Vassar” (615). I can’t help but think that, at the height of nineteenth-century imperialism, “West-washing” paved the way for today’s persistently problematic whitewashing, propagating a worldview in which Western was “right” and “Other” was “wrong,” and in which all non-western cultures could be rectified if only they were marched smartly into a worldwide Western monoculture.

Our Journey Around the World may be, at best, morally gray, but is nonetheless fascinating in its contradictions. It is a “secular” work infused with evangelical fervor, written by people who dedicated their lives to channeling the vigor and enthusiasm of youth into helping others, but who often write less-than-charitably about other peoples. Beautiful to look at and frequently entertaining, the book is also deeply offensive in its depiction of other cultural norms and of non-Western peoples. Reading this work is like riding a psychological roller coaster: one passage, in which Francis Clark wonders at the misinformation that led a young Australian to believe that American women all chew gum and “go around spitting upon the streets promiscuously” (98) elicits a chuckle; a few pages on, a description of three Australian cattle drovers, whom Clark refers to as “tame blacks” and describes in much the same language as the regional wildlife, is like a punch in the stomach.

Yet whether you love it or loathe it, Our Journey Around the World is every bit a product of its time, and can be valued for the historical evidence it provides. Through its pages, we can peer into a late-nineteenth-century power couple’s worldview as they (literally) view the world — a “glimpse of life in a far-off land” if I’ve ever seen one.

_________________

Further reading on the Clarks and the Society for Christian Endeavor:

MacFarland, Henry B.F. “The Christian Endeavor Movement.” The North American Review 182.591 (1906): 194-203.

“Model Constitution and By-Laws of the Young People’s Society for Christian Endeavor.” Toronto: The Endeavor Herald Publishing Co., 1888.

by

by