Holding a rare book is the closest I’ve come to time-walking. Perhaps this assertion seems dubious coming from someone who spent childhood summers chopping rutabaga to be stewed in an open hearth and teaching other kids Nine Men’s Morris in a short gown, cap, and petticoat. (My first foray into living history was as my mother’s shadow when she worked at Indian House Children’s Museum in Deerfield, MA.) Yet I maintain that when you want to immerse yourself in the worldview of a previous century, texts from the period are a good place to start. Often you can find an old text prettily bound, prefaced, and annotated in a modern edition that you simply pull off the shelf of a library or secondhand bookstore and take home. This ease of use affords you the leisure to read and reread, to become acquainted with an author’s language by interacting with the text both intellectually and literally, through underscores, highlighting, or notes (although please, no Mr. Bean moments in the library — keep annotations and alterations to your own books!). It can be freeing to lose yourself in the text of a book without sparing much thought for its material value, and odds are, you aren’t pulling quotes for your Shakespeare final from a 1623 First Folio kicking around your dorm room, but rather from a modern Oxbridge critical edition of the Bard’s works.

The downfall of exploring history solely through uncontextualized ideas is an incomplete understanding of the past. Physical objects can give us some of the best insights into the daily lives of the people who made and used them, and, in a history museum, you can see how inhabitants dressed, worked, ate, interacted, and spent their leisure time. How much closer can you get to a fashionable young English lady at the turn of the nineteenth century than her neoclassical white muslin gown, yellowed with age and faint sweat stains? (Sorry, Nana, ladies don’t just “glow.”) Yet most of us – unless we (a.) go to school to become museum conservators, (b.) inherit illustrious European estates, or (c.) are Lara Croft – do not have the opportunity to touch centuries-old artifacts that our predecessors once wore, held, used, and considered unremarkably commonplace.

Perhaps you’ve deduced where I’m going with this, but here it is nevertheless: the single most amazing thing about rare books and manuscripts is that they house texts and are also artifacts. And – wait for it – YOU CAN TOUCH THEM. An eighteenth-century book not only holds a text that speaks volumes (often three, if we’re talking early novels) about the author’s worldview and the culture that produced it, but also of book production at the time of its publication. Even more invigorating is the fact that someone owned this book, and that perhaps many someones flipped through the same pages you hold in your hand. You can find traces of these people – of a book’s provenance – in bookplates, ownership stamps, inscriptions, marginal notes, and sometimes random scribblings. This is what I mean by time-walking, for I never feel closer to people of the past (whoever and whenever they were) than when I’m holding the same book that they held when it was new. This feeling reminds me of a line from Alan Bennett’s The History Boys, when the boys’ teacher Hector describes the profound connection you have with an author who has written something you’d always thought “particular to you.” Then, suddenly, “here it is,” he says. “Set down by someone else, a person you’ve never met, maybe even someone long dead. And it’s as if a hand has come out, and taken yours” (Bennett 56). I’ve hardly worked in SLU’s rare book room for a month, but already I’ve had the pleasure of clasping many such hands reaching down from the shelves.

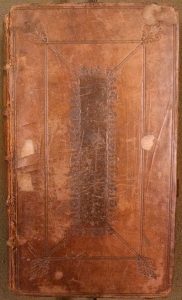

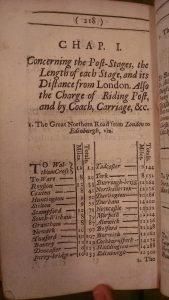

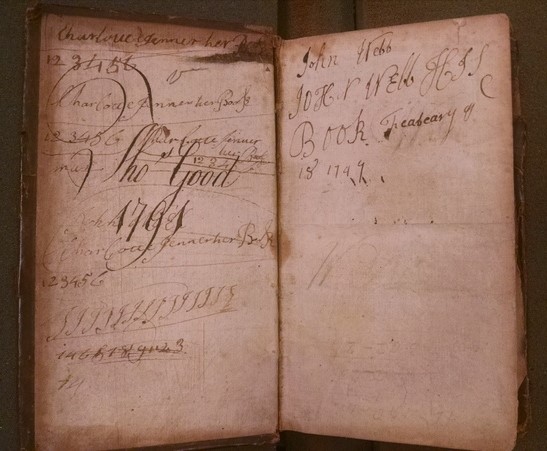

One book that I’ve become particularly attached to is this 1728 edition of British Curiosities in Art and Nature. A travel guide to eighteenth-century England’s counties, complete with post-chaise timetables and calendars listing the dates of annual fairs and events (whoever said we need the internet to plan a trip?), the volume has been caringly bound in calf-skin with blind tooling on the covers and a gold-tooled spine. The title page alone could occupy me all day, with the endless title that helpfully excuses the reader from perusing the whole text (was SparkNotes inspired by pre-industrial subtitles?), the conspicuously absent author, and the clear visual direction to the publisher’s house “under Serle’s Gate” in London. Yet it is the pastedowns and endpapers – spaces left intentionally blank by the publisher – that enchant me. It is on the front pastedown that Charlotte Jenner supplants the anonymous author to take possession of what she has emphatically retitled “Charlotte Jenner her book.” Though the endpapers are rife with hands – at least two others, Thomas Good and John Webb, have signed their names here – Charlotte’s is the name that reaches out to me. Perhaps it has something to do with how she practiced her numbers only up to six, or with the line of j’s she scrawled across the page, trying to get the form of this most crucial letter in her name just right. Perhaps her hand, material and metaphorical, reaches out to me because I remember practicing my own letters in just such a way, laboring over the capital letters that made my name decisive. I can see a young Charlotte Jenner curled over the book, writing slowly and with great concentration, before taking a break to read of the wonders beyond her own small corner of England.

In reality, I have no idea who Charlotte Jenner was. Was she a child learning to write? A young woman proud to own her first book? An older woman practicing her letters? I don’t know where she lived, or even when within the wide window of time after 1728. She wrote nothing profound in British Curiosities – only her name and some numbers. Yet her disregard for this book as an artifact, using a now safeguarded object as her writing tablet, is a reminder that this book was once new. It was to Jenner as your textbooks are to you: a source of information, of text to be interacted with, underlined and doodled beside: both a text to be learned from and an everyday object to be marked proudly as one’s own, but no more to be idolized than a toothbrush. And thus, we come full-circle.

Who was Charlotte Jenner? I don’t know, but she held out her hand, and I took it. So now I ask you: who will you meet in your rare book room?

by

by