What do tending livestock and working in a rare book room have in common? Both have a tendency to make your hands look like this:

Fortunately for me, dirty hands spell job satisfaction. I can’t count the number of times I’ve been mocked by friends, family, and fiancé alike for measuring productivity by the color my hands turn the tap water after a day of work. (At my last job: “I stabilized books for four hours this morning, and my hands were absolutely black. It was great!”) Yet, satisfaction aside, isn’t it curious for books to be so grimy? The inquisitive among you may (understandably) be wondering, why is it that shifting books for an hour leaves your hands roughly as grubby as would weeding a garden for the same amount of time?

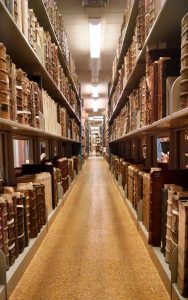

The answer is not that I make a habit of sweeping the floor of the stacks with my bare hands (ew), nor is it that our books are just that filthy. Paper does attract dust, as you may have noticed in your own experience from the fine veil of particles that accumulates on bookshelves at home, and the majority of our collections – which range from incunabula (the earliest printed books, produced before 1501) to current faculty publications – have been around long enough to attract a legion of dust bunnies burrowing snugly beneath dust blankets. Fortunately, thanks to routine collection maintenance, neither we nor the books are living beneath the accumulated airborn detritus of centuries here in the rare book room. We routinely sweep the floors and dust the shelves in rooms where our books live, and valiant student worker Micah Miller vacuumed the edges of materials in our pre-1820 collection as recently as 2011, keeping the dust at bay with the type of vacuum (equipped with a HEPA filter and soft brush attachment) recommended for book cleanings by the Northeast Document Conservation Center (NEDCC).[1] Kudos to his dust-busting (periodic cleanings are an important part of any book conservation program), but the question still remains: what is making my hands so dirty?

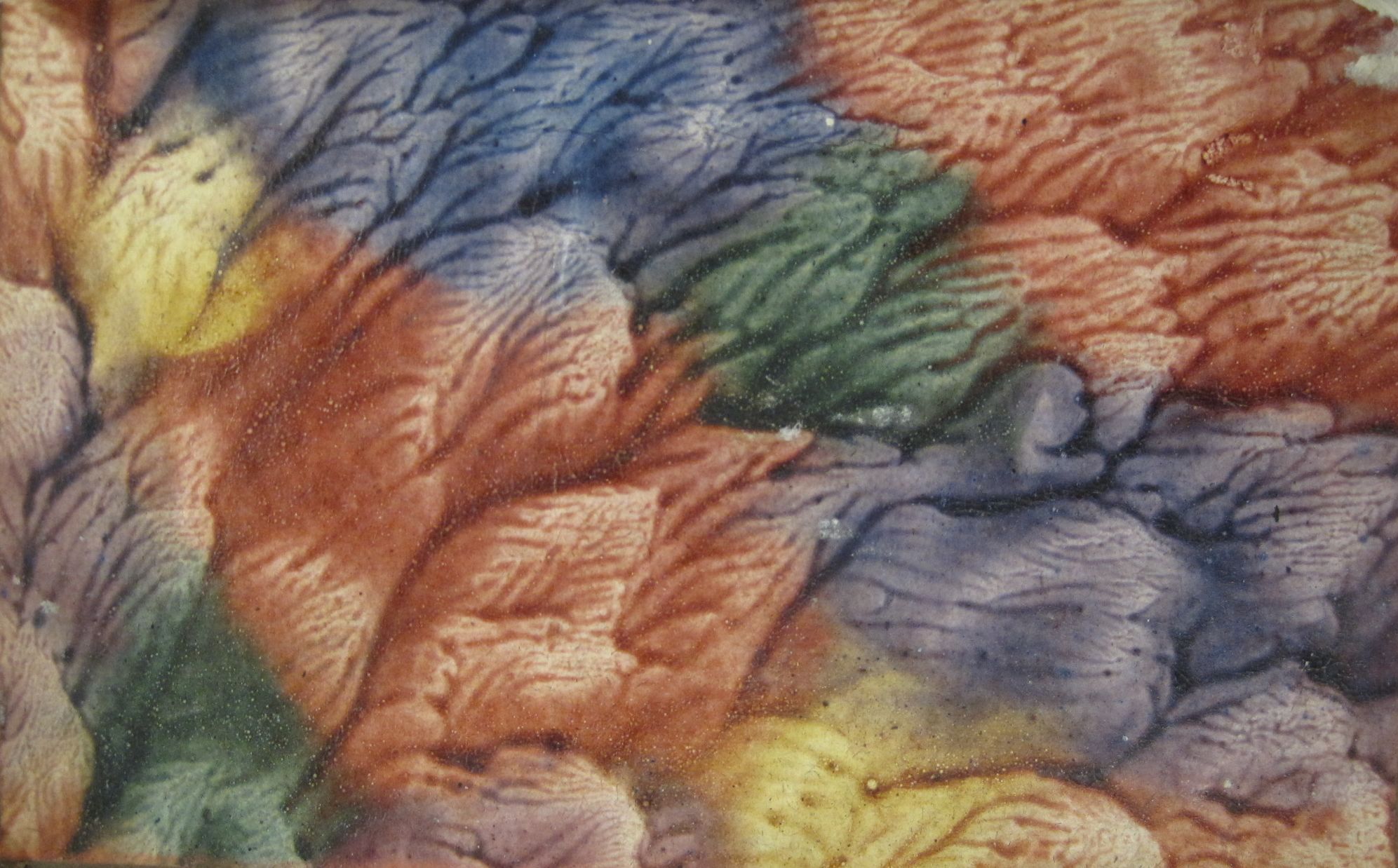

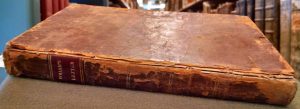

The main culprits are the books themselves, which are made from organic materials plagued by inherent vice. Rakishly exciting though it sounds (Alec D’Urberville, anyone?), in conservation circles, “inherent vice” refers to materials containing agents that naturally cause deterioration over time, independent of outside forces. The treated leather used in most pre-industrial book bindings is prone to gradual decay. The leather absorbs sulfur dioxide from the air and, through a process of oxidation, produces sulfuric acid. The acid weakens the chemical structure of the leather through hydrolosis, which, on a molecular level, breaks down chains of collagen (a protein in animal hide also found in human skin). The visible result of this process is slight cracking of the leather, which gradually deteriorates and comes away in a fine, reddish-brown powder called “red rot” (or, as a former colleague at the University of Illinois used to call it, “mummy dust”).

While red rot results from a natural process, it can be hastened and exacerbated by a number of factors. First of all, the type of animal hide used affects leather longevity. Sheep, calf, and goat skin were all commonly used in fifteenth- to eighteenth-century bindings, and while calf and goat tend to produce fairly hardy cases, sheep skin has a tendency to delaminate – to not only lose its sheen, but to peel away in layers. This is due to differences in a sheep’s coat, which forms a thick, insulating, deep-rooted fleece made up of crimped hair rather than straight (like that of cows and goats).[2] The deep roots of this crimped hair mean that when hair follicles are removed during tanning, sheepskin is left with a tiny gap between dermal layers.[3] As the resulting leather ages, the top layer tends to peel away, leaving the exposed under-layers more susceptible to deterioration.

The original quality of the animal hide will also affect the hardiness of the resulting leather, and agricultural changes in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, in which farmers began to favor larger, more productive livestock over smaller, hardier, and (literally) thicker-skinned animals began to affect leather durability.[4] Additives from vegetable tannins, which came into widespread use in the processing of animal hides during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, have also been found to exacerbate the deterioration process.

Unfortunately, since red rot is a natural process that springs directly from qualities intrinsic to processed leather, there is no known way to treat or reverse it. All we can do is track the deterioration of books in our collection and, when necessary, stabilize or conserve them through the application of supports (such as conservation bands) and enclosures. This is an ongoing project at SLU, where Rare Books staff do periodic sweeps of the whole pre-1820 collection, making note of books’ condition, banding items in need of structural support, and measuring them for custom-made enclosures. The upside? The process of deterioration is a slow one, so these materials should still be around – and available for use, whenever you choose to come look at them – for a long time yet.

For my part, I can look forward to many years of satisfaction in using my “dirty hand gauge” of productivity. Maybe I should look into a patent?

[1] https://www.nedcc.org/free-resources/preservation-leaflets/4.-storage-and-handling/4.3-cleaning-books-and-shelves

[2] http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/collectioncare/2013/09/heres-looking-at-you-kid-under-the-microscope-with-leather.html

[3] http://britishlibrary.typepad.co.uk/collectioncare/2013/09/heres-looking-at-you-kid-under-the-microscope-with-leather.html

[4] http://blog.thepreservationlab.org/2015/01/18th-and-19th-century-leather-a-conservation-challenge/

by

by