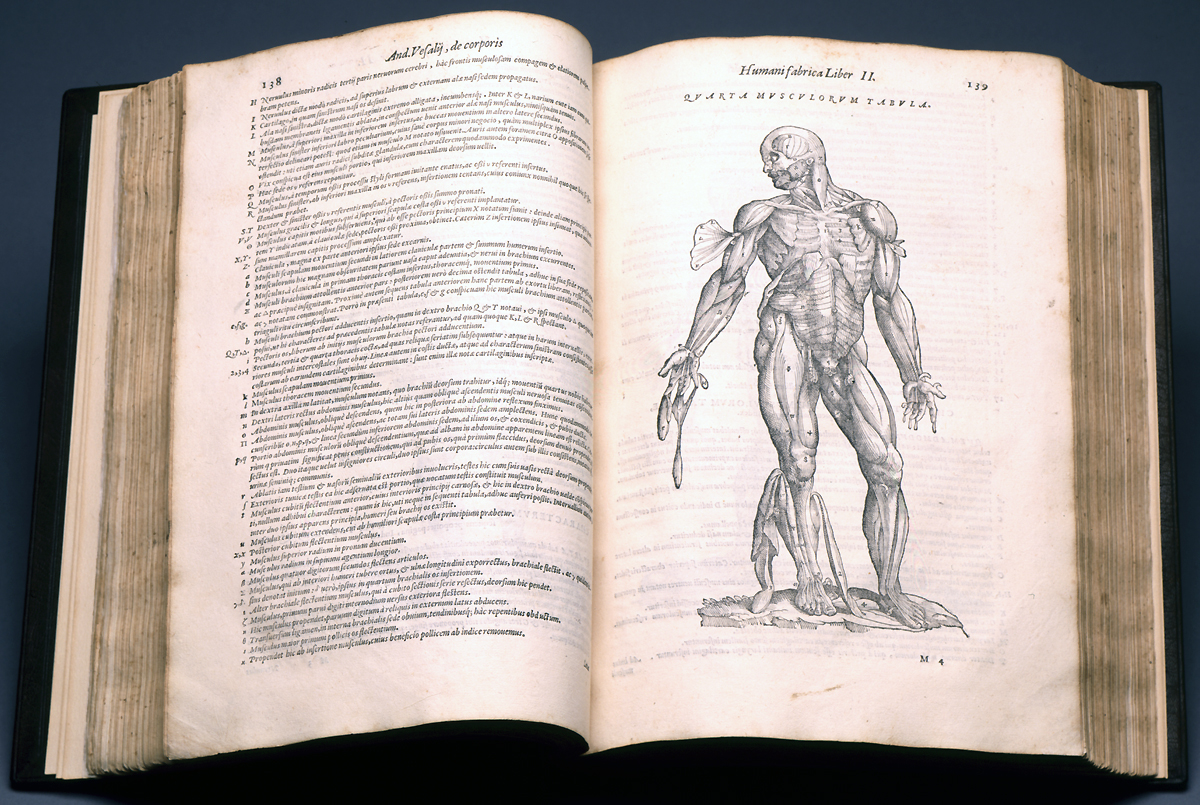

Our books like to keep many secrets (from centuries-old flowers pressed carefully among their pages to the carcasses of bookworms who gorged to death on words), but among my favorites is their hidden cache of vibrant, marbled papers. The art of marbling, which most likely originated in Japan (read about Japanese marbling, or “suminagashi,” here), but first made its book arts debut in sixteenth-century Persia, has always had an air of mystery. This mystique stems in part from the magical quality of the technique, which (counterintuitively) uses a fluid process to imitate stone. Colorful droplets of paint floated on thickened water are combed into a design that is then applied to fabric or paper laid onto the surface of the water. Manipulation of this “floating ink” (as the Japanese aptly name it) is mesmerizing to watch (seriously — check out this video of the process used to make a nonpareil pattern), but easy to replicate. In fact, the basic process of marbling is so simple that early commercial marblers safeguarded their craft by veiling it in mystery. They kept the ingredients used to treat paper, thicken water, and produce certain effects from the public, and doled out the secrets of the art to new craftsmen only sparingly. Guild masters would teach their apprentices only one or two marbling techniques apiece, enabling them to produce a handful of designs without posing the threat of serious competition in a tight-lipped industry working to produce such high-demand art (Loring 17).

The secrecy surrounding the production of marbled paper also affected its spread from east to west. While it appears to have spread naturally (albeit gradually) from Persia, through Turkey, and into continental Europe by the end of the sixteenth century, its initial foray across the Channel to England was just as clandestine and somewhat underhanded. Duties on imported paper were so high at the time that the first marbled papers acquired by bookbinders were imported under-the-radar as wrapping paper for Dutch toys (Loring 19). (If only Amazon packages came wrapped in marbled paper…)

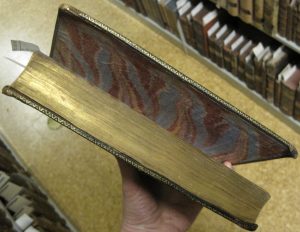

By the seventeenth century, however, what had been a closely guarded decorative technique unknown outside of Japan and Persia had come into widespread use in Europe, and marbling was used to adorn endpapers, both board and leather book covers, and the edges of text blocks. An array of decorative styles and techniques (all of which are pictured in either this handy style guide from the University of Washington or in Iris Nevins’s book Traditional Marbling) developed regionally before coming into wider use. Some common designs in our collection are Turkish Stone, French Snail, Stormont, French Shell, and Fine-combed (or “Nonpareil”).

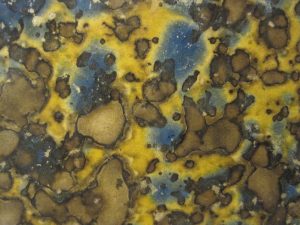

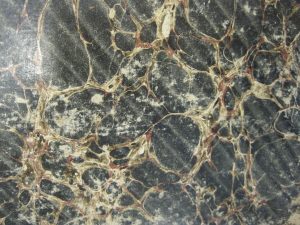

The most technically basic marbling design is Turkish Stone, a pebbled pattern achieved by dropping paint on the water and applying it to paper without further manipulation. This technique was popular in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Variations on the pattern include Stormont and Shell, both of which involve mixing additive into the dye to produce specific effects. Stormont, a design technique of the mid-eighteenth century, uses turpentine, which, when mixed with the body color (the color applied last to the water solution and therefore most prominent on the finished paper), produces a lacy effect. Shell, on the other hand, is achieved when the marbler mixes his dyes with oil. The oil prevents the dye from spreading far across the size (the thickened water), and creates patterns of concentric circles in which the body color nests.

Spanish Marbling is another design that begins as a simple stone pattern. A striped overlay effect is created by rocking the paper gently back and forth as it is laid on the size. (Interestingly, legend has it that the first Spanish Marbled pattern was a mistake, resulting when one marbler jostled the trough of another just as the second was a laying his paper onto the size. I’ll stick with my favorite story, though, which attributes the pattern to a hung-over seventeenth-century craftsman whose shaky hands prevented him from transferring paint cleanly from size to paper [Loring 27].)

The French Snail pattern has been used on endpapers since the mid-seventeenth century, and, browsing through our seventeenth- and eighteenth-century books, its popularity is apparent. “Snails” – small, curled waves drawn at intervals to further embellish another design – crawl across numerous pages in our pre-1820 collection.

Finally, Fine-combed patterns, created when the teeth of a comb are run through a stone design, have been popular since the introduction of marbling into Europe. The earliest designs are in light, whimsical pastels, while older, nineteenth-century revivals of this classic design favor a dark palette of predominantly deep red.

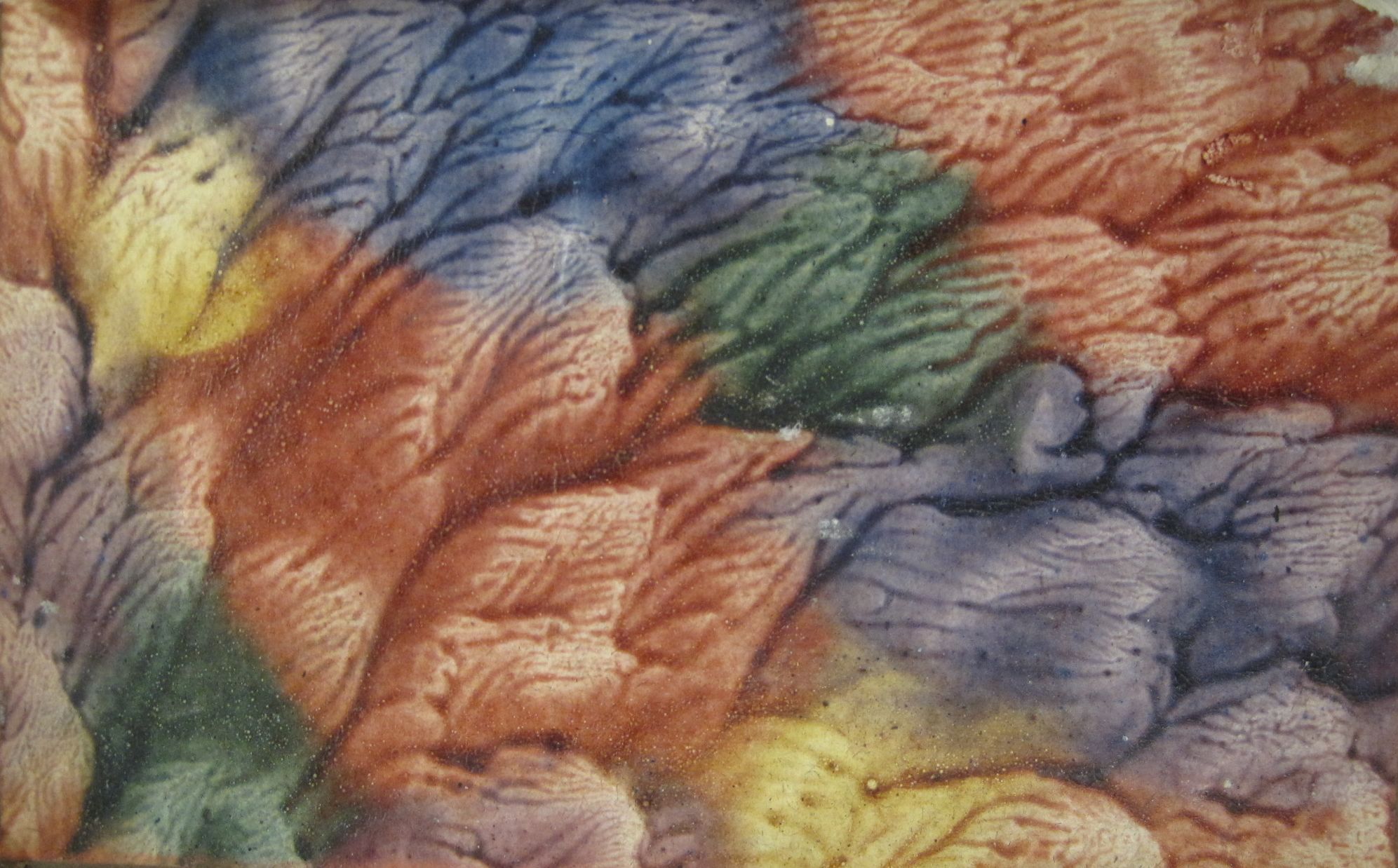

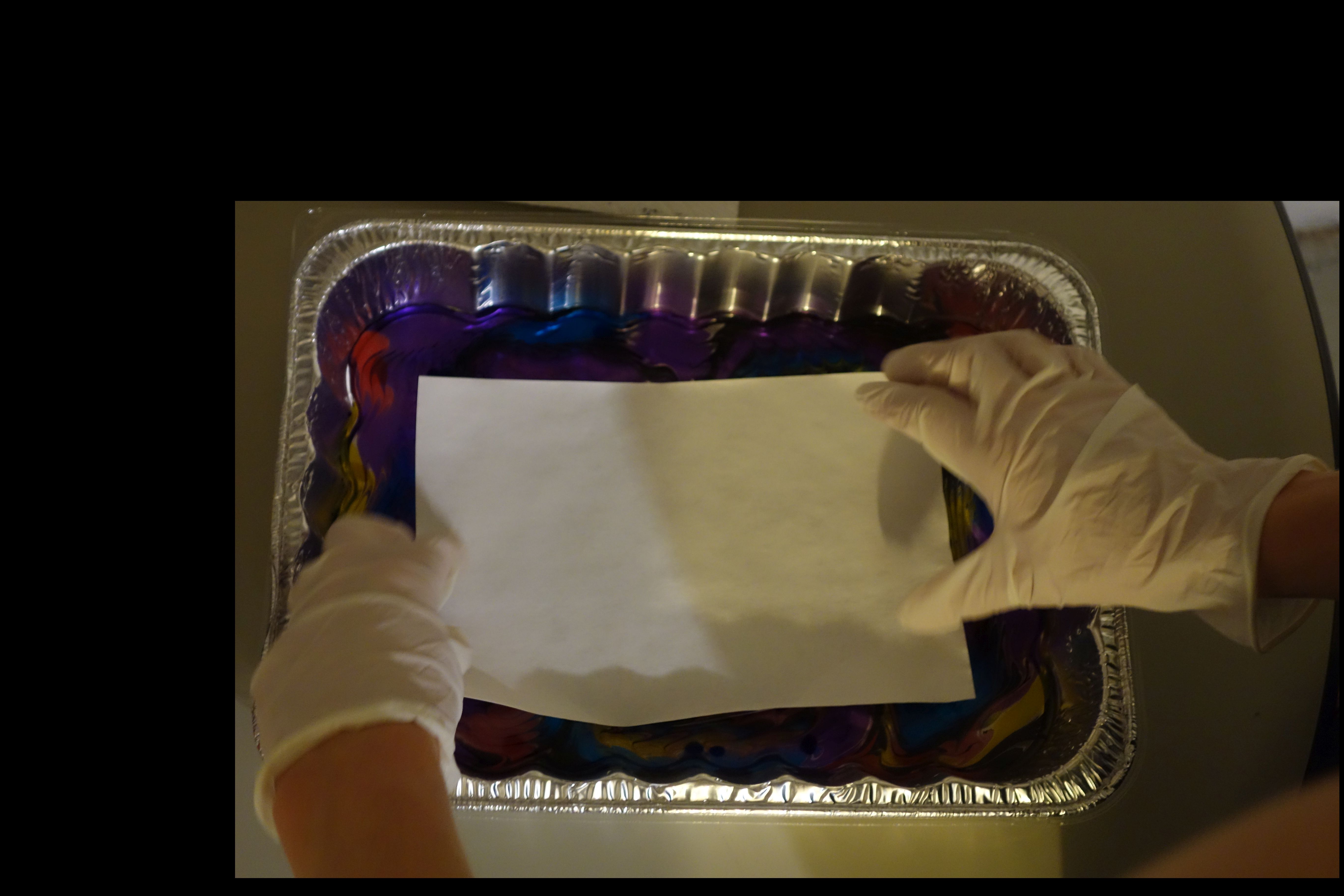

I don’t know about you, but the beauty and vibrancy of these old patterns, combined with the seeming simplicity of the process used to make them, left me with the hankering to try marbling myself. Now that the art is no longer a closely guarded secret, marbling kits for beginners are available in most art supply stores. I found my Jacquard Marbling Kit on Amazon, but you can find a number of options from numerous vendors. The kit contains alum (which, when dissolved in water, is used to treat paper so that paint adheres to it) and carrageenan (or “Irish moss,” a seaweed derivative used to thicken water so that paint floats on its surface), as well as several paint colors. The set-up was as simple as expected: I simply soaked paper in an alum solution, mixed the carrageenan with water, and went crazy with the colors! Clearly, I have a natural talent for marbling. See how closely my pattern mimicked the intended fine-combed design?

Better luck next time, I suppose – and there will definitely be a next time! For now, I invite you to come see some fine examples of marbling in SLU’s collection (there’s so much more than what is pictured here) and, hopefully, to take inspiration for your own marbling adventures.

by

by