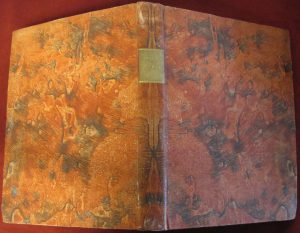

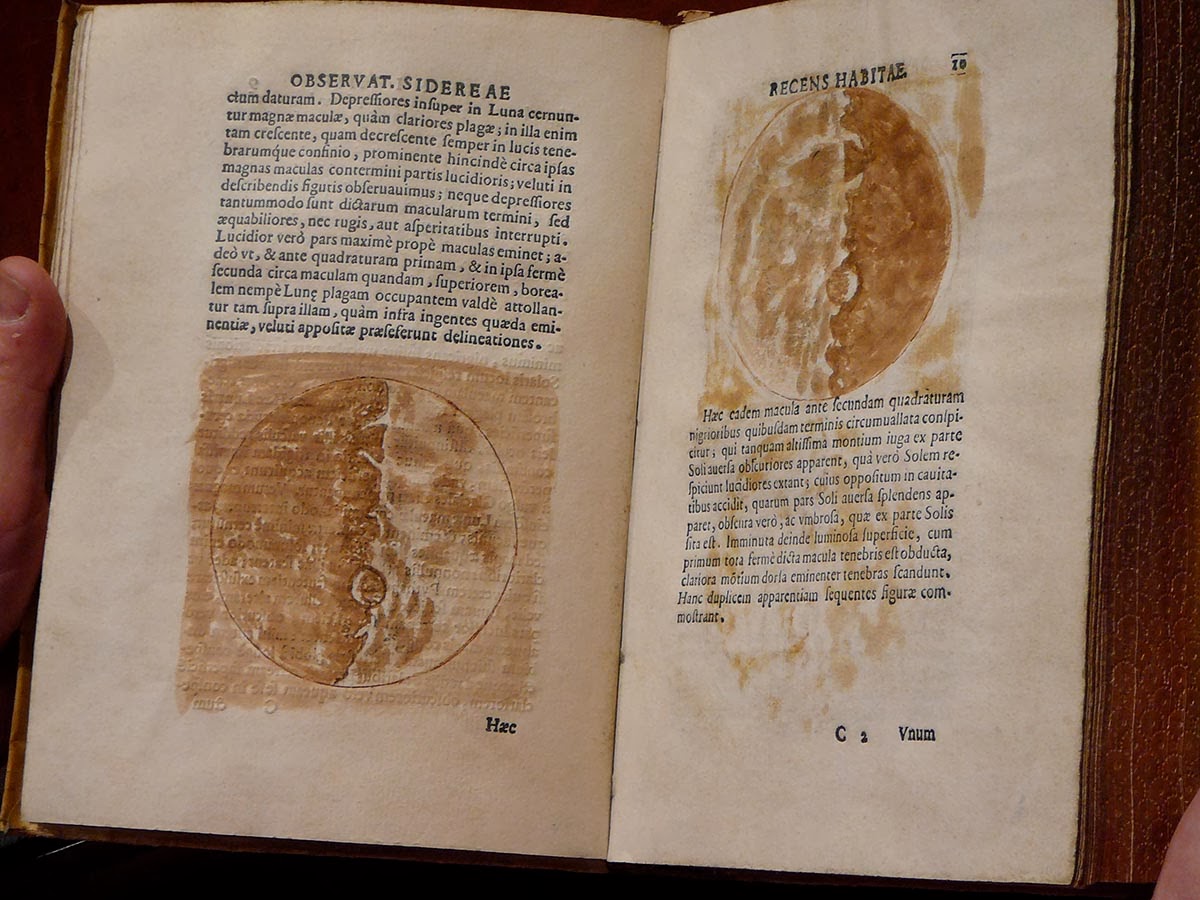

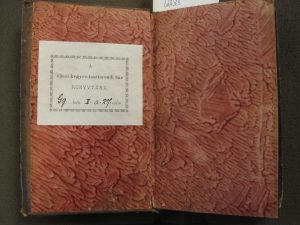

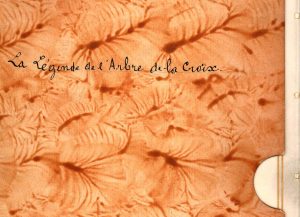

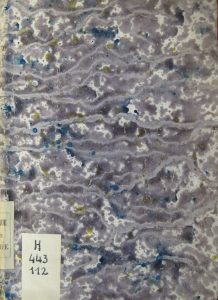

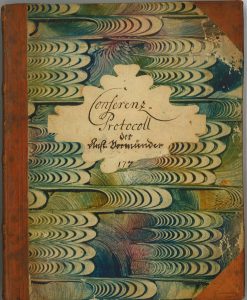

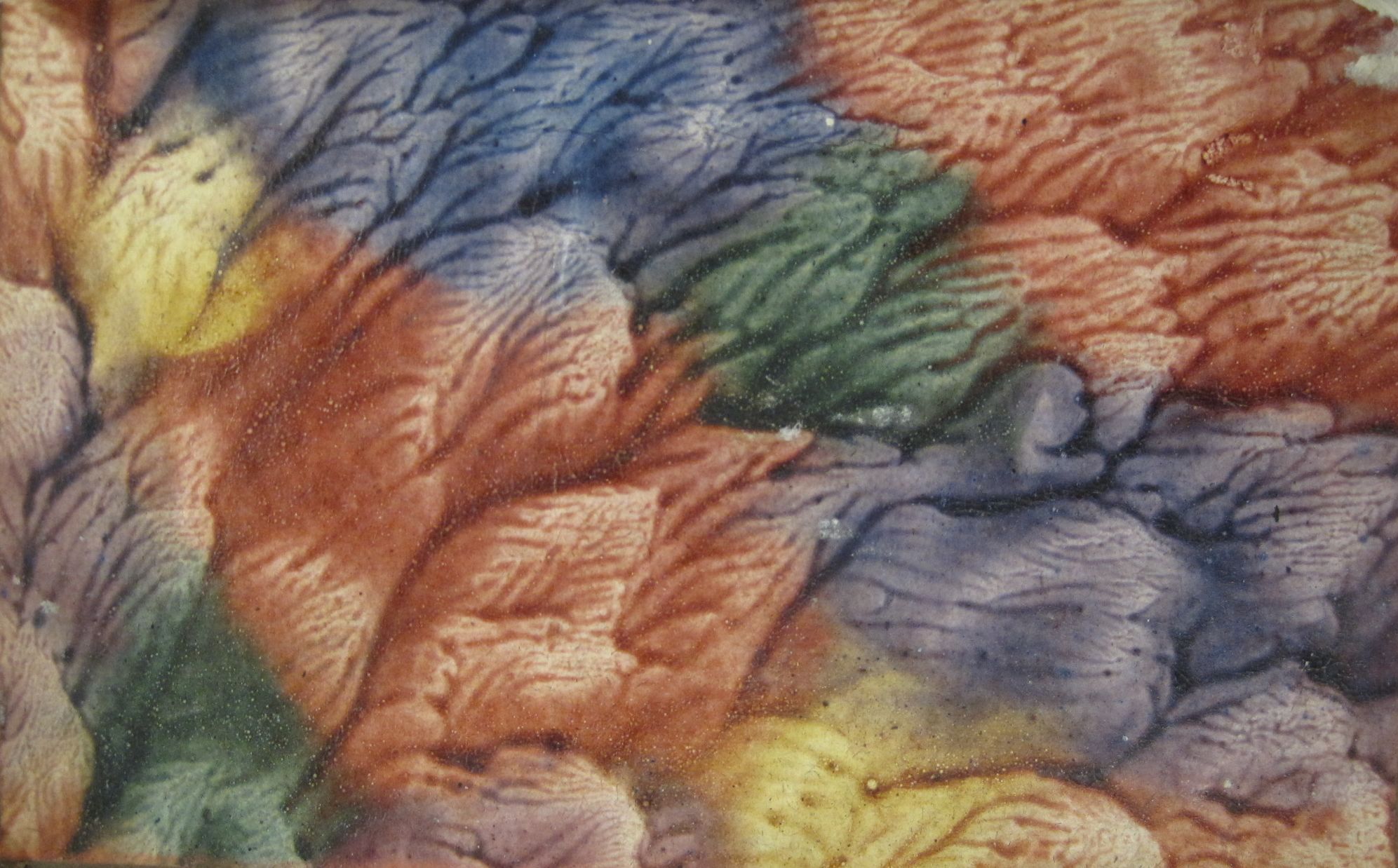

What do these two images have in common?

They may share neither a color palette nor a design, but both depict paste papers found in eighteenth-century bindings. Such papers — some boasting bright shocks of color, others dull or faded — are scattered throughout the covers, end papers, and edges of SLU’s rare book collection. After marbled and printed papers, they are the most prevalent type of decorative paper in our stacks.

What exactly is paste paper, you may well ask? It is paper decorated with thick paint made from colored pigment and starch paste in a process often compared to finger painting. Makers need only a simple starch (such as wheat, corn, or rice flour), water, and a source of heat over which to mix the two until they thicken into (you guessed it) a paste. When the paste cools, it is combined with enough water-soluble paint to obtain the desired hue. A brush is then used to spread the colored paste across a dampened sheet of paper. Once the paper is evenly coated, various tools can be used to manipulate the paste into patterns simple or complex. The decorative process is very forgiving, for the long dry-time of the thick paste mixture allows the artist ample time to play with his or her design before it hardens. When the design is deemed complete, the paper is hung on a line to dry, usually overnight. It is then ironed flat and ready for use.

Paste papers can generally be broken into five main categories by method of decoration. Pulled, drawn (including combed), daubed, and printed pastes all begin in the standard way, with a sheet of paper evenly coated in paste. In making spatter paste (as well as two subcategories of the first group, Spanish daubed paste and prints in paste), the paste paint design is applied directly to blank paper with a tool rather than worked onto a sheet evenly coated with paste.

Pulled paste, a popular base design from the sixteenth century on, is made by coating two sheets with paste and laying them, paste-sides together, one on top of the other. The artist rubs the top sheet, then immediately peels it off the bottom sheet to produce a feathery, veined design.

Felt shapes or yarn might also be laid between paste-coated sheets, and appear, palely and indistinctly, in the finished pattern.

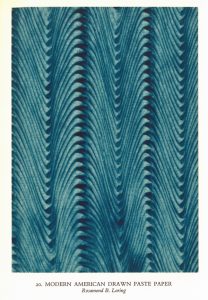

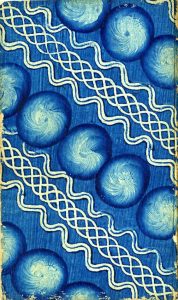

In drawn paste, nearly any household object (or the artist’s fingers) can be used to draw designs across a paste-coated sheet of paper.

Daubed paste designs are made using sponges. In the most widespread tradition, a paste-covered sheet is dabbed with a sponge to create a textured design, but in the Spanish style, the sponge is used to apply paste to a blank sheet of paper.

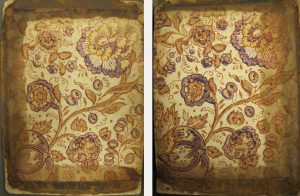

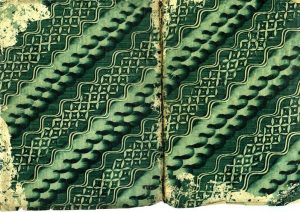

Printed paste borrows from the printed paper tradition, and relies on stamps or woodblocks to impress designs into paste-covered sheets. Designs cut in relief appear lighter than the surrounding paste, while intaglio designs are darker and more distinct.

Alternatively, prints in paste can be made by applying paste – sometimes in multiple colors – directly to a woodblock. The design is stamped onto the paper as it would be in standard printing.

Spatter paste, in which paste thinned by water is splashed onto the page from the bristles of a paintbrush, creates the most random designs. If the paper is hung to dry while the paste is still quite wet, the paste will run.

Paste paper examples can be found in books dating as far back as the sixteenth century, and many rival their better known marbled paper contemporaries in vibrancy and creativity of design. So why don’t we hear more about them? While paste paper’s popular contemporaries, marbled paper and printed paper, left a trail of production evidence, such as the woodblocks used to print designs and the records of the Parisian guild of dominotiers (makers of decorative papers), paste papers have left little trace – beyond their existence – on the historical record. This is, perhaps, because paste paper is far less glamorous (and demanding) than the marbled, Dutch gilt, and printed paper starlets of the decorative paper world. The marbling process required precise measurements of expensive ingredients (such as ox gall), and was sensitive to everything from impure water to changing air temperature; printed paper production required the right tools, and successful operations relied on skilled woodcarvers to produce a continual supply of woodblocks that could be mixed and matched in a variety of printed designs. Paste paper, by contrast, required only common and inexpensive ingredients, and was not susceptible to the vagaries of temperature and humidity. Making paste paper required “but little skill or experience” (Loring, “Colored,” 40), which meant that binders and booksellers could easily produce their own in-house. Paste paper became the logical choice for binding ephemeral publications (such as pamphlets), and was an economical option for small printing operations unable to afford professionally made decorative papers. Thus, paste-paper making was a craft of common knowledge: few (if any) paste recipes were written down, and papers were nearly always unsigned.

It wasn’t until the eighteenth century that a known European paste-paper-making operation began to produce stylistically distinct papers. From 1764 to 1825, the Sisters of Herrnhut (a group of unmarried women living in a strict Moravian Church community in Herrnhut, Germany) produced blue, red, and green paste papers using a mix of drawn and printed techniques. Little is known about the Sisters’ business or about the individual craftswomen, but the venture supplied a local demand for decorative papers and provided work for a community that not only valued hard work as a form of religious devotion, but required sixteen-hour workdays of all its able-bodied occupants. Their characteristic style – what Richard Wolfe calls “the Herrnhut way” of using woodblocks to make printed paste patterns (Wolfe, 201 n. 32), a method originally borrowed from printed textile manufactory (Berger, “Rosamond,” 15) – became extremely influential, for the layering of techniques in their designs exhibited the potential for true artistry and sophistication in paste paper. Aided by missionary work, both the Sisters’ papers and their methods of making them soon began to spread, and by 1800,“Herrnhutter Paper” had became almost synonymous with “paste paper.”

Though papers produced or influenced by the Sisters of Herrnhut can be found in many libraries’ collections, the Sisters’ legacy reaches far beyond any bookshelf. Not only did they establish a tradition of paper-crafting in their own community (a tradition that lives on in the manufacture of the twenty-five-pointed Herrnhuter Moravian star), but they paved the way for twentieth-century paper artists like Rosamond Loring and Veronica Ruzicka. By coaxing paste paper designs and techniques to reach new heights of sophistication, these women advanced and professionalized the craft, bringing it to broader public attention by providing decorative covers for limited editions issued by major publishers.

If this whirlwind tour of paste paper has inspired you to learn more about its history – or, better yet, to add your own designs to this four-hundred-year-old decorative tradition – then Rare Books is planning an event for you! From 4:00 p.m. to 5:00 p.m. on Wednesday, April 6th, the Rare Books reading room (Room 307 of Pius XII Memorial Library) will be home to a paste paper workshop. We will examine eighteenth-century paste papers from SLU’s rare book collection, discuss how to produce various paste paper designs, and make our own drawn, pulled, and printed paste papers. Materials will be provided free of charge, and we’ll have many paste paper examples on hand to help kick-start your creativity.

All SLU students, faculty, staff, and Library Associates are welcome to register for the event beginning on Monday, March 28th at noon.

We hope to see you there!

____________

References:

Berger, Sidney E. “Paste Papers.” Conversant: The Phillips Library at the Peabody Essex Museum. Peabody Essex Museum, 20 July 2015. Blog post.

—-. “Rosamond B. Loring’s Decorated Papers.” Marbled and Paste Papers: Rosamond Loring’s Recipe Book. By Rosamond Loring. Cambridge: Houghton Library, 2007. 11-29. [Rare Bks Ref. Z 271.3 .M37 L67 2007]

Dürninger Textil Druck. Web.

Hutton, J.E. A History of the Moravian Church. London: Moravian Publication Office, 1909. [Pius Microfiche BT10 .A8 no.1988-0692]

Loring, Rosamond B. “Colored Paste Papers.” The New Colophon: A Book Collector’s Quarterly 2.5 (1949): 33-40.

—-. “Paste End-Papers.” Decorated Book Papers. Cambridge: Houghton Library, 2007. 65-70. [Rare Bks Ref. Z 271 .L85 2007]

Marks, P.J.M. An Anthology of Decorated Papers: A Sourcebook for Designers. [Rare Bks Ref. NK 8553 .M37 2015]

Sutter, Sem. “Wrapped in Color: A Survey of Paste Paper Bookbindings.” University of Chicago Library Special Collections, March 1994. Exhibit catalog.

Wolfe, Richard. Marbled Paper: Its History, Techniques, and Patterns. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1990.

Zaehnsdorf, Joseph William. The Art of Bookbinding: A Practical Treatise. 1890. Farnborough: Gregg International Publishers Limited, 1969. [Rare Bks Ref. Z 271 .Z17 1890a]

by

by