Women’s History Month seems an apt time to explore the myriad ways in which women are represented — as authors, artists, subjects, printers, binders, and former owners — in the works of SLU’s rare book collection. In this installment of “Students in the Stacks,” doctoral candidate Ben Halliburton considers one such way in which women (or rather, their bodies) are represented in the historical record: as the subject of scientific speculation. Join Ben as he looks at De Secretis Mulierum (On the Secrets of Women), a popular late-medieval guide to the workings of the female body, and considers the potentially far-reaching effects of the text’s long-accepted misinformation.

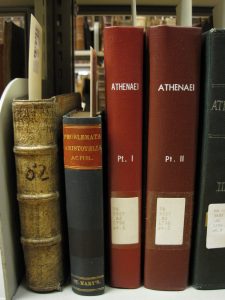

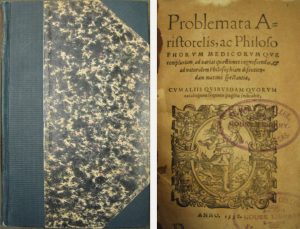

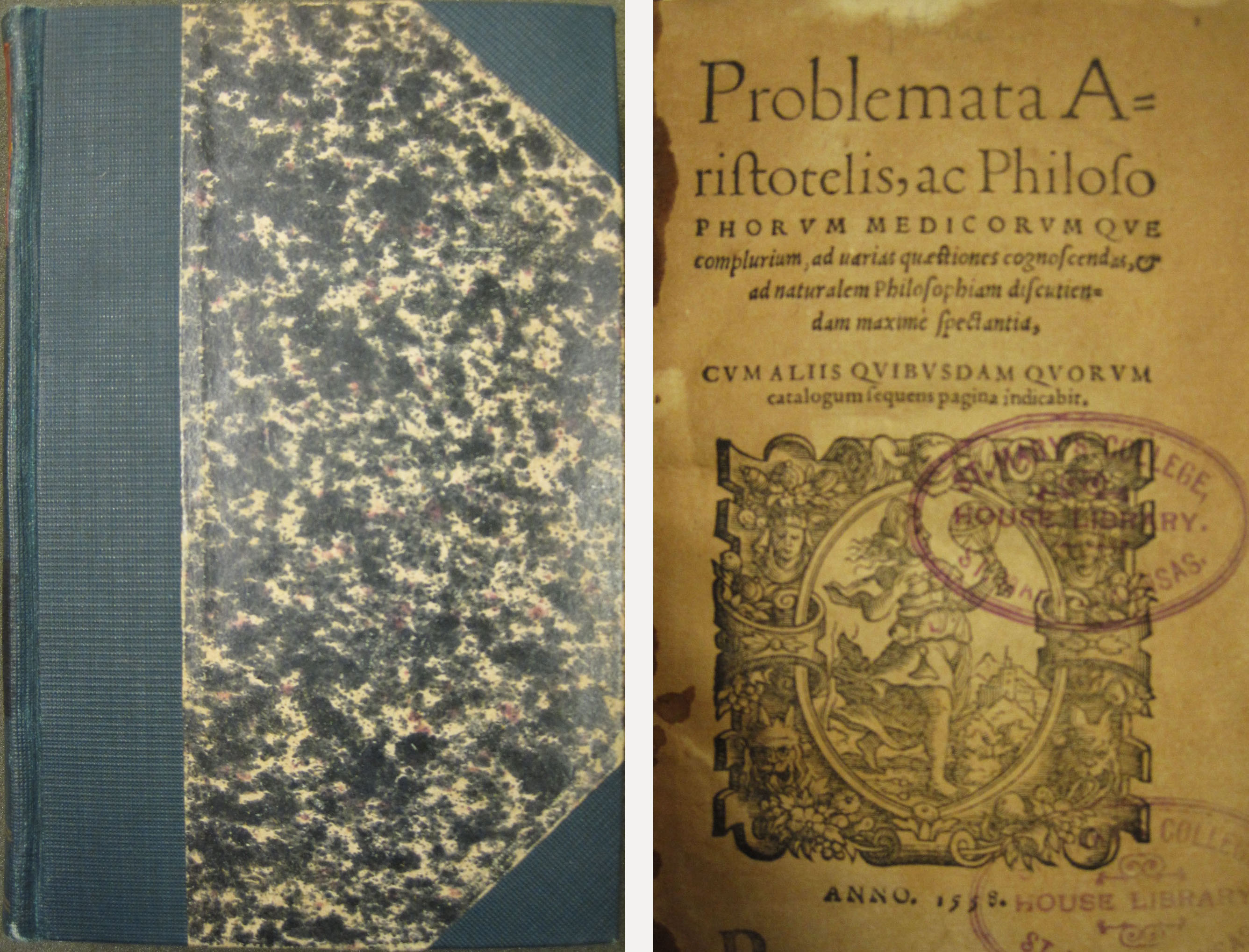

The first thing that struck me about De Secretis Mulierum was the title. It certainly wasn’t the book itself, which isn’t terribly remarkable to look at. It’s somewhat small for an octavo, in an old library binding of three-quarter green cloth over marbled boards. The red label on the spine announces its contents to be the Problemata of Aristotle, an eclectic collection of questions and answers not actually by the great Greek philosopher himself. If you were walking through the stacks, you could easily pass it by. I know I did several times.

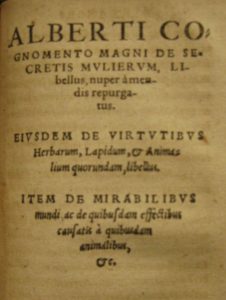

But as I looked through the online catalog, the book’s second title caught my eye immediately. On the Secrets of Women by Albertus Magnus, saint and teacher of Thomas Aquinas? I had never heard of it, but I immediately set out to learn more.

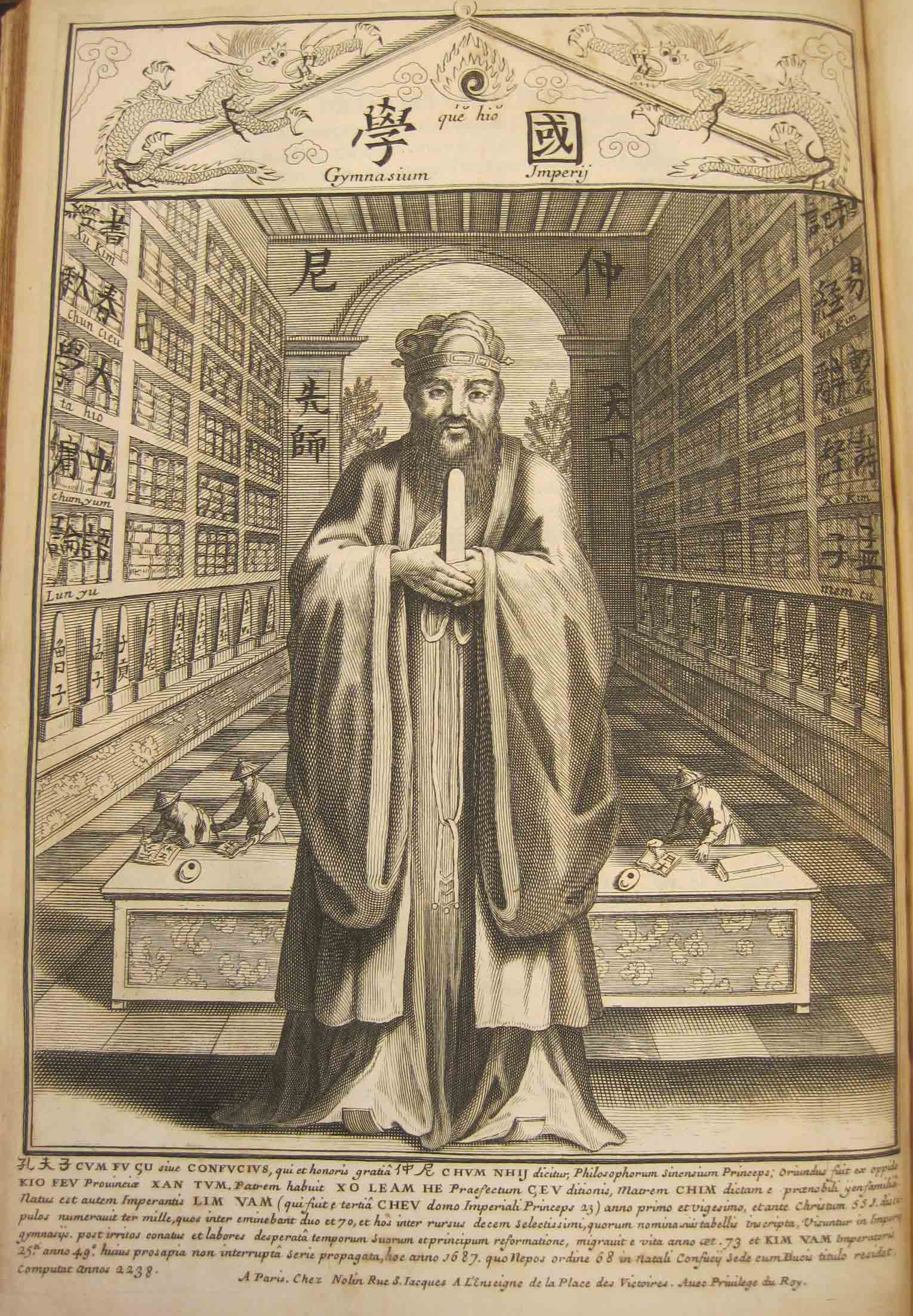

First thing’s first: the work is not actually by Albertus Magnus. It includes some selections of his writing, but the rest is an anonymous work put together some years after his death. The title, however, is more accurate. De Secretis Mulierum does tell you about all the weird and crazy things that a woman’s body does. At least, it tells you about all the weird and crazy things that medieval monks thought a woman’s body did.

A lot of the text involves astrology, which is not that surprising if you’ve read any medical or quasi-medical text from the Middle Ages or the Renaissance. Much as the sun touches Earth with its heat and light, other heavenly objects were thought to influence life, though in subtler ways. This sounds silly to us, with what we now know about the universe, but it would have been seen as irresponsible back then for a scientist, philosopher, or doctor to ignore any potential influence on events. Accordingly, if perhaps overzealously, the anonymous author of De Secretis Mulierum describes the many different ways that he thinks the stars and planets affect an unborn child. A child born under Jupiter will be beautiful and kind, but a child born under the constellation of an animal might be born with that animal’s head!

There are pages and pages of this stuff, but not much in the way of medical testimony, which the anonymous author repeatedly claims to have lacked the time and space to include. This omission may have been partially due to physical limitations, but was probably more a result of the work’s intended audience. After all, the stated intent of De Secretis Mulierum is not to cure women of anything, but to convey information about them – not all of it necessarily factual – to the curious monks. It’s no surprise that this work about women reads as though it were written by a man who hadn’t spoken to a woman since he was a child.

The anonymous author’s treatment of menstruation is a good example of how he did not allow his ignorance to impede his intentions to inform and explain. Menstruation was seen almost as a consequence of original sin, which left women’s humors imbalanced and made them sources of pollution for everyone around them. Menses were thought to result from women’s inability to digest food properly, owing to their innately cold and wet humor. This belief was reinforced by some misunderstanding over what orifices were involved in the process. When a woman was pregnant or nursing, the waste food normally released through menstruation was converted into milk to feed the child. It wasn’t thought that there had to be anything particularly special about a woman’s body to make her capable of child-bearing, as there were many contemporary reports of flies, mice, and snakes being spontaneously generated from undisturbed refuse. A human baby couldn’t be that much different, could it?

Of course, philosophical speculation based on a vague knowledge of Aristotle and of female bodies wasn’t confined only to De Secretis Mulierum. The tendency of a woman’s womb to wander around the body, whether metaphorically or literally, was accepted by many others in addition to our anonymous author. Two centuries after De Secretis Mulierum was published, experienced physician Anthonius Guainerius even wrote a book about the wandering womb called Tractatus de Matricibus! The author of De Secretis Mulierum didn’t get much right, but even up until the twentieth century, when “hysteria” finally ceased to be a common diagnosis for women, few people did.

It’s important for us to remember that books are powerful vehicles for understanding, but also that this understanding can sometimes be faulty. This text, often bundled with apocryphal Aristotle, was popular for centuries, mostly because it outlined a simple problem (we don’t know much about women) and gave a simple solution (let’s avoid them) with a simple rationale (they’re probably dirty and/or evil). The consequence of this popularity, so Helen Rodnite Lemay tells us in her introduction to Women’s Secrets, was a climate of confusion and suspicion surrounding women, which in turn provided fuel for the witch-hunts of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Our copy of De Secretis Mulierum may be easy to overlook on the shelf, but the historical impact of this work and others like it is hard to ignore.

by

by