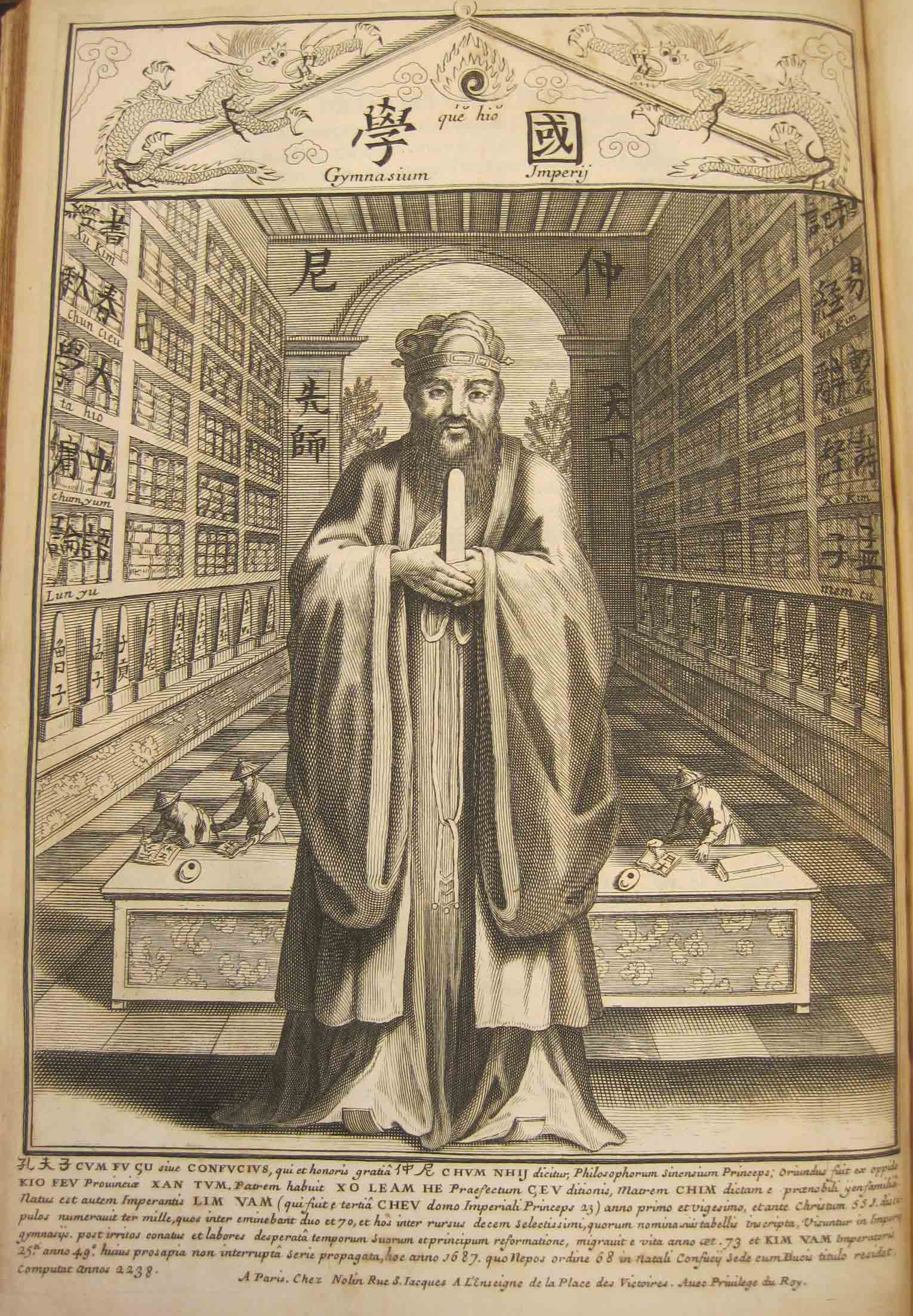

Are you attending Friday’s lecture by Ronnie Hsia on “Confucian Christianity” in the Matteo Ricci Speakers Series? Then you will be interested in today’s installment of “Students in the Stacks” by doctoral student Ben Halliburton, in which Ben gives the background on an important Jesuit work in our holdings, the 1687 Confucius Sinarum philosophus.

The examples in history of one culture meeting another for the first time are few, but they come easily to mind. We think of Columbus stepping off the Niña onto the shores of Hispaniola, of Livingstone laying eyes on Victoria Falls in Zimbabwe, of Marco Polo traveling a continent to the court of Kublai Khan. These are moments of discovery, but they aren’t the only way that two cultures come into contact. Sometimes it’s more subtle, through the written word.

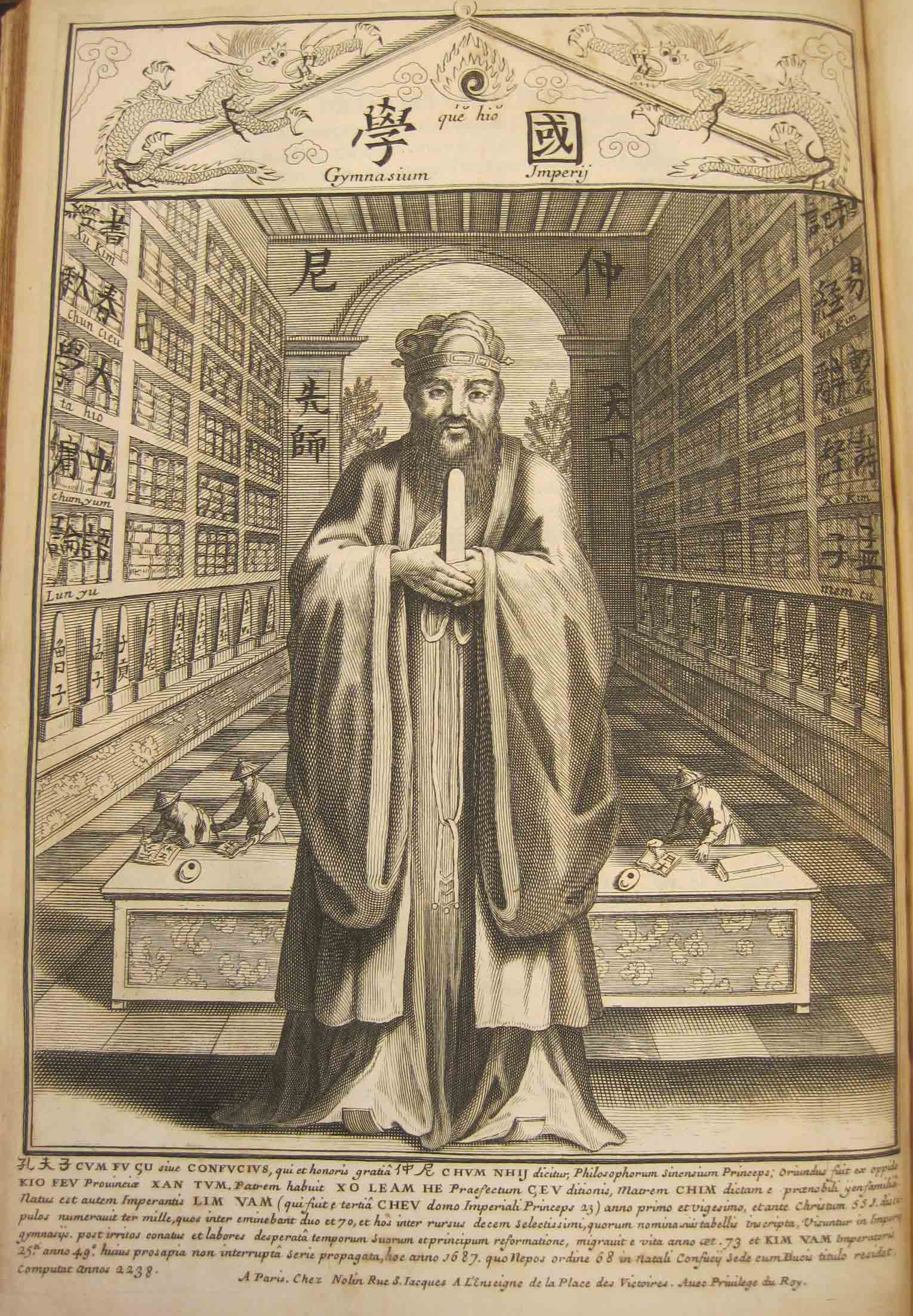

This book, the Confucius Sinarum philosophus, has a century-long story behind its creation, going back to the arrival of the Society of Jesus in China during the late sixteenth century. When Michele Ruggieri and Matteo Ricci started educating other missionaries on the language and culture of China, they did it through the translation of the Four Books, the foundational texts of Confucianism. At first, these works were chosen because they were part of the civil service examination that dictated the Chinese sociopolitical hierarchy, which the Jesuits sought entry into, but Ricci especially came to see Confucianism also as a philosophical framework, within which Christianity could make itself part of Chinese culture. In the years before his death, he began to encourage more formal translations of Confucian works, in the hopes of producing an authoritative collection for distribution and analysis.

However, after Ricci’s death, the purpose of the translation project quickly changed. Dominican and Franciscan friars, who had begun to arrive in China by the mid-seventeenth century, challenged the Jesuit policy of accommodation and assimilation of Confucian ritual into Christian theology. They argued that Confucianism was superstition among the lower classes and atheism among the upper classes, both of which were antithetical to Christian missionary work. To refute these claims, the translations of the Four Books, well over half a century old by this point, now had to go about proving their own orthodoxy instead. Several promising young Jesuits, among them Philippe Couplet, worked feverishly on the manuscript, which was finally sent to publishers in the Netherlands and Rome in 1670.

As the rites controversy escalated, Couplet made the long and dangerous journey from China to Europe in order to make the case for an expansion of the Jesuit mission. When he arrived in 1684, he found that the manuscript still hadn’t been published. Couplet decided to revise it himself, mostly by removing “digressions” that he found to be too heretical on reflection, and then went looking for someone to publish it. He’d hoped to have it published in Rome by a papal press, as a way of demonstrating its orthodoxy, but that didn’t work out. Instead, he appealed to the French royal court. King Louis XIV had just revoked the Edict of Nantes, restoring his status as “most Catholic” king, and was the next best thing to the pope for Couplet. Luckily for him, Louis was eager to enjoy the prestige that came with having a piece of the Far East with his name on it. He gave Couplet five thousand livres to finish the work and had it published by the Bibliothèque Royale in 1687. And that’s how we get the book in front of us today.

When you open the book, the front page immediately makes you aware of the king’s hand in it. The device on the title page is three fleurs-de-lis, the French royal emblem, after all. An unknown but apparently huge number were printed, all opening with a dedication praising the king of France for his wisdom and generosity. As far as public relations go, it was a victory for Louis.

The content of the Confucius Sinarum philosophus has just as much of an agenda, namely defending its use by the Jesuits, but it isn’t any less impressive for that. The hundred-page introduction presents Confucius as a philosopher somewhere between Cicero and Aristotle in terms of importance, but also with a relationship to the Chinese like Moses for Hebrews and Muhammad for Muslims. Even the biography of Confucius, which mostly repeats the traditional account from the Spring and Autumn Annals, ends with a comparison to St. Paul using pagan Greek philosophy to spread Christianity. You can see how anxious the Jesuits were to defend Confucius as an ally in their missionary efforts.

Still, there are many exciting places in the text where we can see Eastern philosophy and culture being transmitted to the West for the first time. For instance, Couplet explains the basic principles of Taoism, another philosophical and religious tradition in China, in his introduction, including a description of yin, yang, and how they combine to form the eight elements of Chinese cosmology. In the back of the book, there’s even a chronology of the “kings” of China along with a map of East Asia. All in all, it was a complete work that represented the sum knowledge of the hundred years the Jesuits had spent there.

More than anything, the Confucius Sinarum philosophus represents a truly epic clash of cultures, not with swords but with words. For perhaps the first time in the history of Western civilization, the philosophical tradition of one culture was used to provide context and interpretation for the philosophical works of another culture. What’s more, the Jesuits did it in plain and simple Latin that had been refined over a century of work and that could be read by anyone in Europe. In fact, many people did read it, helping to spark what has been called the Sinomania of the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries. It wasn’t just common people who caught the bug while drinking tea out of porcelain for the first time. It spread even among intellectuals like Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who developed an obsession with Confucius and the I Ching.

And we have here the work that started it all. If you’re interested in seeing the Confucius Sinarum philosophus for yourself, come visit it right here in Rare Books!

–Ben Halliburton

by

by