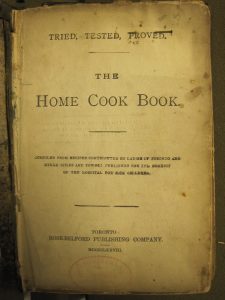

Thanksgiving approaches, and my thoughts have turned to one of my favorite books in SLU’s collection: The Home Cookbook: Compiled from Recipes Contributed by Ladies of Toronto and Other Cities and Towns (1878). Last year, I surveyed the contents of this well-worn domestic manual, noting elements – a section on table etiquette, an interlude of short stories, a list of recommended kitchenware and appliances, and a section of home remedies – that set it apart from modern cookbooks. Setting The Home Cook Book in the broader context of women’s history, I considered how compilation cookbooks such as this gave average women the rare opportunity to record their own small piece of family history and to see their names in print.

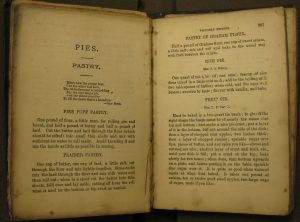

While I am still fascinated by The Home Cook Book as a source of historical evidence, I decided that this year, I would put the book to more practical use by bringing one of its recipes to life in a modern kitchen. Skipping past the pickled oysters and matrimony sauce (because some things are better laid to rest), I decided to focus on the chapter about pies. The Home Cook Book contains three recipes for pastry and 34 for pie. These range from enduring North American favorites (such as pumpkin and apple) to less familiar recipes like “Rice Pie” (a variation of custard pie filled with a rich rice pudding). “Lemon Pie” and “Mince Pie,” for which there are nine recipes apiece, appear to have been the overwhelming favorites. Some of these recipes wouldn’t necessarily appeal to modern taste buds (my mouth puckers at the thought of “Cranberry Tart,” and I’ll pass on the “two pounds of boiled tongue” (214) included in Mrs. Samuel Platt’s “Mince Pie”), but for the most part, they’re fairly recognizable – or, at the very least, decipherable – to twenty-first-century diners.

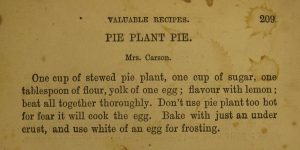

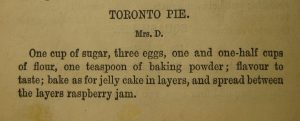

Two recipes that stand out from the crowd are “Pie Plant Pie” and “Toronto Pie.” Since I had no idea what the end result of either of these recipes might be, I promptly decided that I would have to tackle one of the two.

“Pie Plant Pie” was soon ruled out, for its greatest allure was its mysterious main ingredient, “one cup of stewed pie plant” (209). The recipe itself shed no light on the identity of this plant, but in consulting Alan Davidson’s Oxford Companion to Food (2014), I soon found that “pie plant” is an American name for rhubarb (680). Not super exciting, and – more importantly – not in season. I moved on to my final mystery: “Toronto Pie.”

This pie recipe is somewhat puzzling, as it makes no mention of pastry, crust, or cases. The reader is simply given a list of ingredients, then instructed to “bake as for jelly cake in layers, and spread between the layers raspberry jam” (216). Bake like cake and spread jam between the layers? Is it just me, or does this sound distinctly less like pie than like Victoria Sponge? I brought the recipe home to find out. (Disclaimer: enamored as I am with the evidence of use in this compilation cookbook, I have no intention of adding to its charming array of spatters and stains. The book did not leave the library, and I worked entirely with photographically reproduced recipes.)

Proceeding as though this recipe were for cake, I mixed the ingredients (sugar, eggs, flour, baking powder, and lemon zest) and poured the resulting batter in a greased, 8-inch round pan. In true nineteenth-century cookbook fashion, the recipe gives no temperature or bake time (and even if it did, I’m not sure how smoothly they would transfer over to a modern oven). As the resulting “pie” sounded so similar to a layered sponge, I borrowed the oven temperature (350°F) and bake time (25 minutes) from baking icon Mary Berry’s recipe for Victoria Sandwich. A toothpick test indicated that the cake was baked after 25 minutes, but (as it caved in slightly as it cooled and had a somewhat chewy texture) it probably could have used a few more minutes.

When the resulting “pie” (read: cake) cooled, I sliced it in half to make two layers. Then, I whipped up a batch of raspberry jam using an Epicurious recipe as a guide, but reducing the sugar. Finally, I spread the jam on the bottom layer and replaced the “pie’s” lid.

The verdict? “Toronto Pie” is a very sweet, somewhat uninspiring cake, but it’s certainly the most memorable “pie” I’ve ever eaten.

by

by