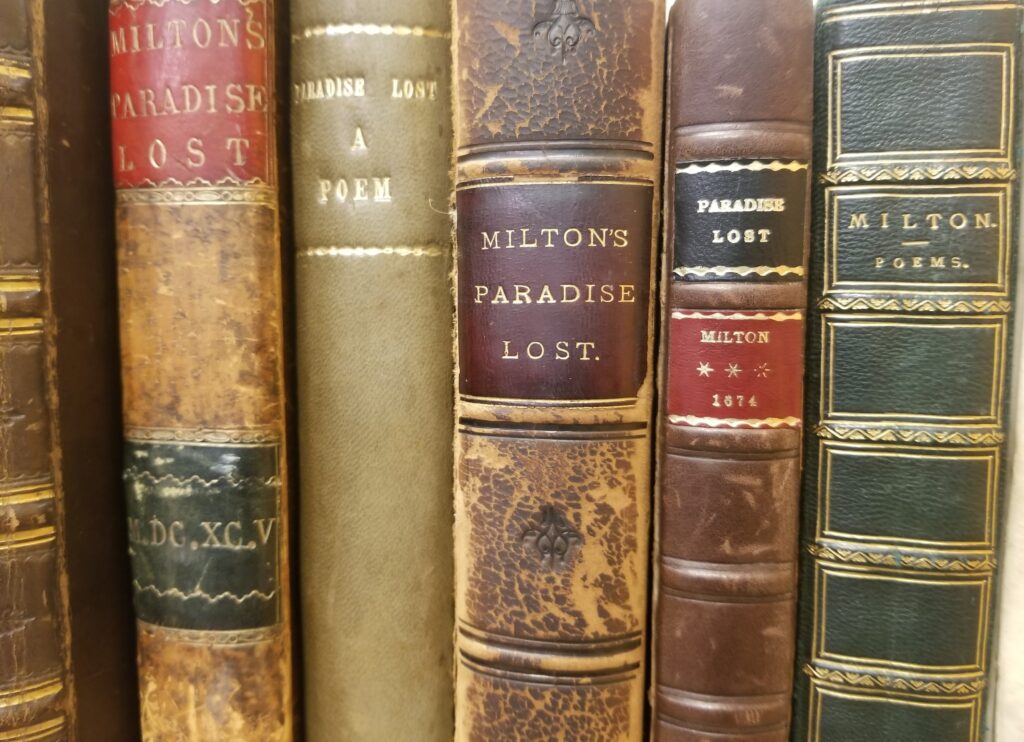

This past June, Saint Louis University hosted scholars from around the world for the 2022 Conference on John Milton. A special session, the Geraghty Symposium, was held in honor of John and Melissa Geraghty, who have generously donated many rare editions of John Milton’s works to Saint Louis University. The conference provided an opportunity for the Rare Books Division of Special Collections to exhibit many of these works, share their fascinating print histories, and consider how they contribute to Milton’s poetic legacy. We continue the discussion of those editions in today’s blog post.

An examination of print history suggests that great poets are not born; they are made—made by the tremendous efforts of printers, booksellers, editors, critics, illustrators, scholars, and even readers, whose wrangling and “behind-the-scenes” assistance plays a large part in catapulting the author’s name into the public domain. This seems to be the case with John Milton, whose rise as one of the most prominent writers of the English language began rather modestly and can be documented in the print history of the early editions of Paradise Lost.

Milton spent several decades of his early career as a civil servant to the Commonwealth and had composed numerous verses, tracts, and translations, but it was Paradise Lost—published when he was in his late fifties after the Restoration—that secured his legacy. Trained rigorously in the Classics, Milton sought to create a poem of national stature that could rival or even surpass the Iliad, Odyssey, and Aeneid. The scope of the project was enormous: if ancient Graeco-Roman poets looked to Classical heroes to craft their “national epic,” Milton went even further back in time—to a Biblical age that preceded human history itself, back to a time when Satan rebelled against God, and Adam and Eve lost Paradise.

Setting out to “justifie the wayes of God to men” (1.26), Milton tells the story “of Man’s first disobedience, and the fruit of that forbidden tree, / whose mortal taste brought death into the world, and all our woe” (1.1-2). The result was an epic of astounding complexity, one that was lofty and Latinate in style, didactic in its theology about goodness and evil, reflective of English Protestantism, and featuring a deeply complex Satan figure—a rebellious, diabolical, persuasive, contradictory, and mesmerizing antagonist who has captivated centuries of readers.

Milton’s poetic ability and placement today in the English literary canon is undeniable. Scores of writers later on, from Romantic writers to post-modern poets, would be influenced by Milton’s Satan, his narrative of origins, and the contemplations about human nature and human flaws. Yet the early printing history of Paradise Lost reveals that his ascent to literary fame was a rather gradual one—at least in the beginning—and aided by a great deal of toil from his booksellers and printers. Today’s post discusses that printing history—the story of the key figures and early publication strategies that enabled the proliferation of the poem.

Samuel Simmons and the First Editions of Paradise Lost

Paradise Lost was initially something of a gamble for Milton’s bookseller, Samuel Simmons, who was unsure if an English Biblical epic would be able to sell. Simmons paid Milton £5 prior to the print run, and their contract stipulated an additional £5 for every additional 1,300 copies sold. The first edition of Paradise Lost, issued over the years 1667, 1668, and 1669, was a relatively modest affair; it was printed as a smaller quarto without any illustrations, and the reader went from title page to text without much embellishment in between.

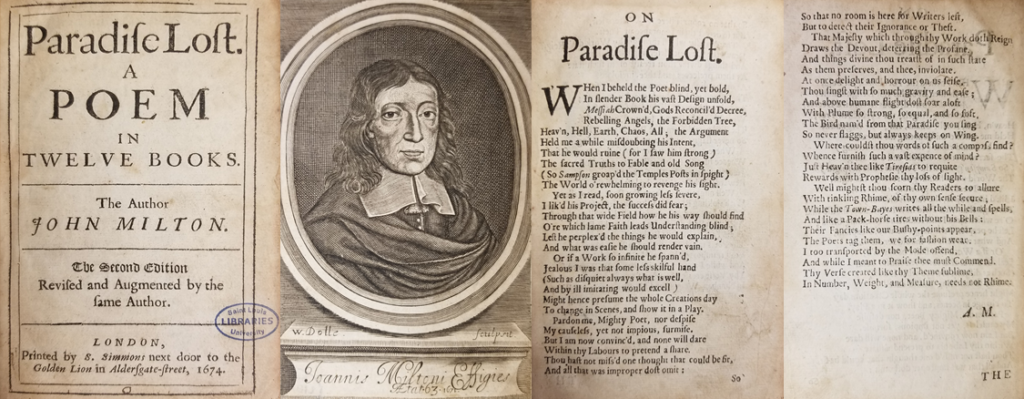

If bolstering Milton’s fame meant that more copies could be sold, subsequent editions certainly began ramping up the paratextual embellishments. The second edition, printed seven years later in 1674, introduced a frontispiece with an engraved portrait of Milton—allowing buyers not only to read the text, but also to visualize the poet. The second edition also enlisted praise from Milton’s contemporaries to vouch for the poem’s literary merits—namely with commendatory verses printed at the beginning by the physician Samuel Barrow and the poet Andrew Marvell. Milton’s bookseller, Simmons, also began including his own name on the title page for the first time, effectively associating his printing house with Paradise Lost—something not done in the first edition.

Milton died in 1674, shortly after the release of the second edition, which became the final version that he had direct editorial control over. He made significant structural changes and divided the poem’s original ten books into the twelve-book format that is standard today. Books VII and X, the two longest books from the first edition, were split in two. This formal restructuring may indicate Milton’s desire to align with Classical and Christian conventions—to follow in the footsteps of the twelve books of the Aeneid or possibly to allude to Jesus’s twelve apostles, but certainly does seem to reveal Milton’s hyperawareness of his relation to poetic precedence.

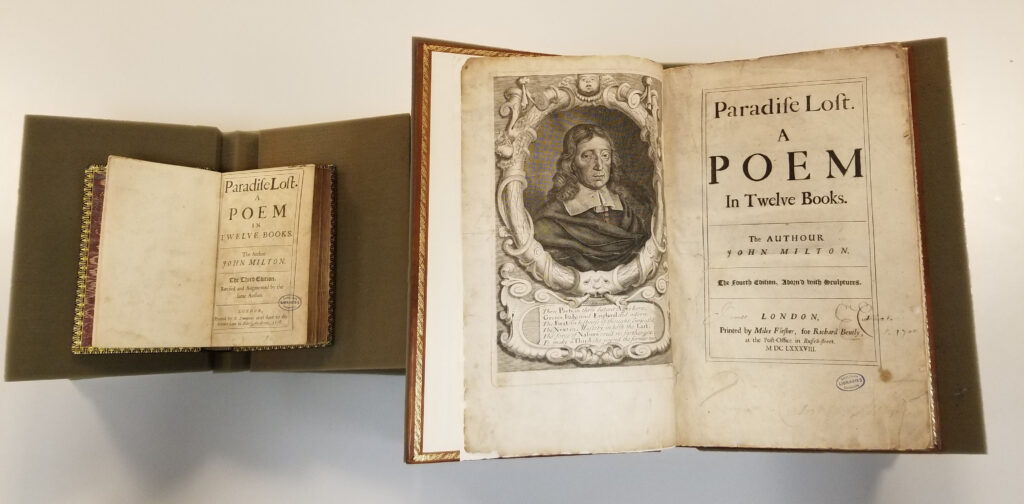

Four years after Milton’s death, the third edition was released in 1678 and, like earlier versions, was printed in a smaller format—as an octavo. It was around this time that the copyright began changing hands—revealing that Paradise Lost, while steadily being printed, was not necessarily a bestseller for booksellers just yet. After the third edition, Samuel Simmons paid Milton’s widow Elizabeth for two additional print runs and then, with a final payment of £8, acquired the complete copyright by the 1680s. Yet Simmons did not keep the copyright, instead opting to sell it off to Brabazon Aylmer. From Aylmer, ownership over the copyright was divided and again sold, passing separately onto Jacob Tonson and the printer Richard Bently. Title pages printed after the third edition sometimes indicate Tonson, sometimes Bently, or occasionally both as the bookseller.

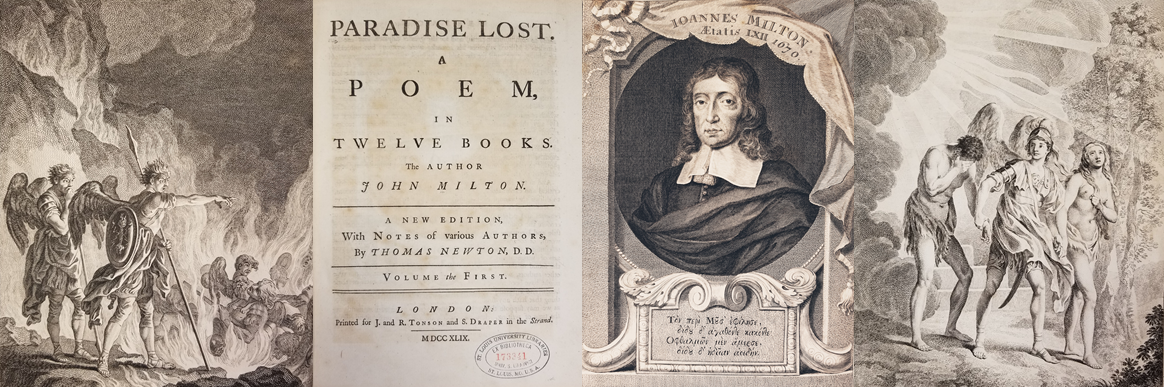

Jacob Tonson and the Extravagant Fourth, Fifth, and Sixth Editions

It was the young Jacob Tonson—only 28 years old when he first acquired half the copyright for Milton’s epic poem—who made drastic printing decisions that consolidated Milton’s legacy in the English literary canon. Milton was already known in elite literary circles, but Tonson’s fourth edition in 1688 is largely considered the decisive edition that made Milton a household name. Everything about it was extravagant: it was the first edition printed in large folio format, the first to have illustrations, and the first to be published by subscription. And Tonson enlisted as many hands as he could for the fourth edition by locating several artists and engravers: John Baptiste Medina and Michael Burghers respectively designed and engraved the majority of the illustrations that now prefaced each of the twelve books, with Bernard Lens and some unattributed hands (possibly Henry Aldrich) for the remaining.

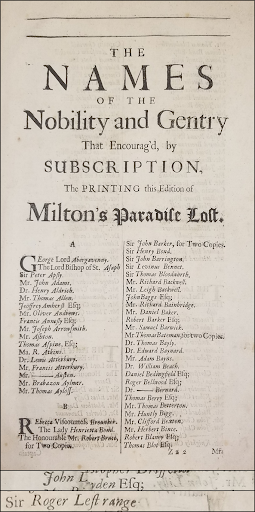

The visual extravagance of the fourth edition was made possible through subscription publication, a system in which booksellers promised copies with certain dimensions or features that readers could pay for in advance. Because early subscribers assisted in offsetting the initial printing costs, their names would then be included in a list within the volume. The fourth edition of Paradise Lost is considered among the earliest examples of subscription printing in the English language. Included in Milton’s subscription list are the names of over 500 individuals, including notable figures such as the poet John Dryden and even Milton’s political foe Roger L’Estrange. By using the subscription system, Tonson not only secured the capital to print a luxurious edition, but he was also able to circulate Milton’s name amongst the wealthy and powerful. The addition of an epigraph by John Dryden placing Milton on equal footing with Homer and Vergil further bolstered Milton’s name.

Jacob Tonson acquired complete copyright over Paradise Lost after the fourth edition and continued printing the poem in folio size with the same engraved illustrations for the fifth and sixth editions. The fifth edition of Paradise Lost was bound together with its sequel, Paradise Regained, for the first time. The sixth edition—considered the first collective edition of Milton’s poetry—joins Paradise Lost together with Milton’s other works, including Paradise Regained and Samson Agonistes.

Paradise Lost’s elevated status as a poem worthy of scholarly study also becomes increasingly evident by the time of the sixth edition in 1695, which introduces meticulous annotations to the text. Jacob Tonson had enlisted P.H., believed to be Patrick Hume, to begin annotating the Biblical and Classical references in the poem. The scholarly Annotations contains over 300 impressive pages of notes alone and stands as a separate accompaniment to the poem. Translations of Paradise Lost also began proliferating, and quite notably, translations into Latin—the language of scholarship in the seventeenth century—likewise began to appear. Milton was no longer just a poet of his time, but a poet to be studied after his time.

Reflecting on the success of Paradise Lost and his role in its legacy, Jacob Tonson writes in a dedication page to the Baron of Evesham in 1705, “It was your Lordship’s opinion and encouragement, that occasioned the first appearing of this Poem in the Folio Edition, which from thence has been so well received, that notwithstanding the price of it was four times greater than before, the sale increased double the number every year. The Work is now generally known and esteemed…” With this, Tonson takes credit for helping to make Milton’s name, but Milton too made Tonson’s name. After the fourth edition, printing Paradise Lost became a lucrative enterprise, and Tonson’s business would grow into an empire that spanned three generations of Jacob Tonsons: Tonson’s nephew (Jacob Tonson the Younger) would succeed the business, and thereafter Tonson the Younger’s son, also of the same name. During the eighteenth century, the Tonsons would become known as printers of preeminent English poets, including Dryden, Congreve, Addison, Steele, and Shakespeare.

Critical Editions: Bentley, Newton, and the First American Edition

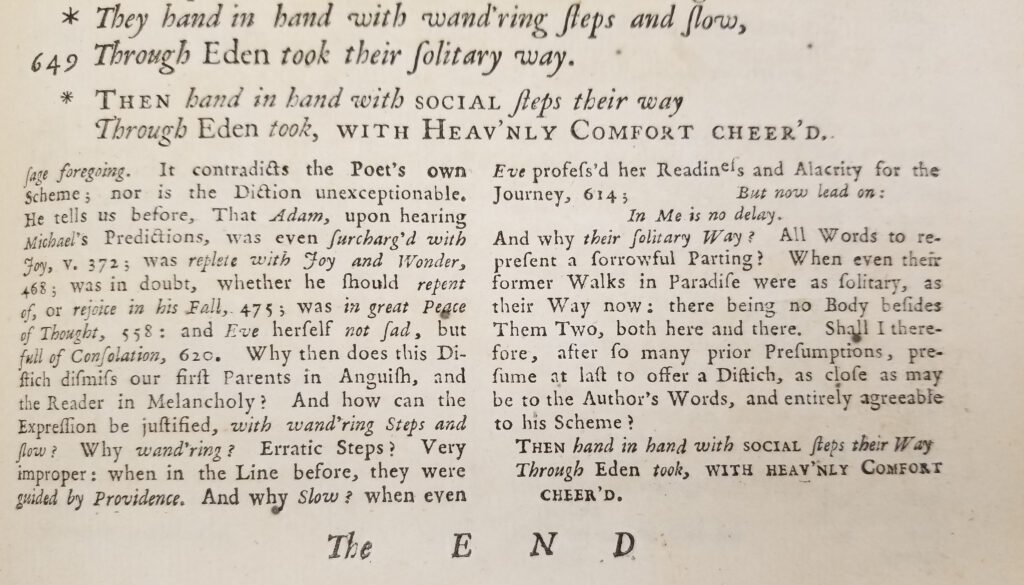

Following the sixth edition, a number of critical editions with scholarly names attached to them began emerging in the eighteenth century. One of the most curious critical editions of Paradise Lost was put forth in 1732 by Richard Bentley, a Classical scholar who took many editorial liberties and heavily modified the original poem to satisfy his own grammatical and stylistic preferences—even changing important Miltonic moments, including the ending lines of Paradise Lost. Bentley argued that since Milton was blind during the poem’s composition, his amanuensis must have made errors in the manuscript, and he even suggested that an editor must have corrupted the text.

As a result, Bentley changed entire phrases and replaced words he thought were unsuitable throughout the poem, despite the fact that Paradise Lost was a modern text printed less than seventy years before Bentley’s own time. Bentley’s case might be considered one of raging audacity—in assuming that he somehow knew Paradise Lost better than Milton himself, but it is also one of scholarly acumen, albeit rather misplaced zeal: Bentley was approaching the text from the academic tradition of a Classicist trained in textual criticism. Like many Latinists and Hellenists who worked with ancient fragmentary texts and were accustomed to “filling in the gaps” with textual emendation, Bentley approached the modern Paradise Lost in the same way.

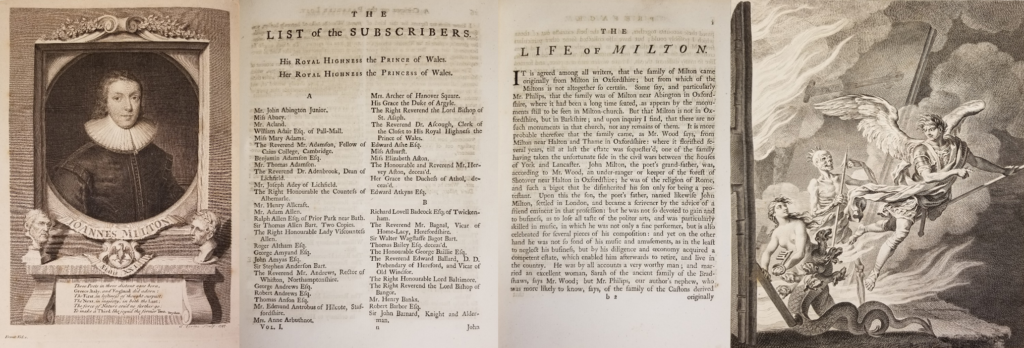

In 1749, Thomas Newton edited a critical edition of Paradise Lost that stood out for its scholarly precision with extensive footnotes as well as a biography of “The Life of Milton.” Dissatisfied that editors had taken so many liberties and made excessive textual emendations to the poem, Thomas Newton, who later became Bishop of Bristol, wanted to remain as faithful to the original text as possible. He drew from the first two editions of Paradise Lost, which he considered “Milton’s editions.” Newton’s version is notable for its footnotes; some are his own, but many are collated from previous commentators, including those of Hume, Addison, Bentley, and Pearce. It is considered the first definitive “variorum” edition of Paradise Lost.

The Newton edition was a hefty two-volume compilation laden with paratextual and reading apparatuses: commendatory verses, dedicatory pages, a biography, Joseph Addison’s criticism, the text itself, footnotes, an appendix, an index, a subscription list, and newly engraved illustrations were all included. This comprehensive edition enjoyed tremendous popularity with several pages of subscribers, including none other than the Prince and Princess of Wales listed at the top of the subscription list. The edition was reprinted numerous times and became the standard library edition in the second half of the eighteenth century.

So authoritative was the Newton edition that parts of it were grafted onto later editions. Although Tonson had issued the Newton edition, it was also around the middle of the eighteenth century that the Tonsons’s six-decade copyright monopoly over Paradise Lost began to loosen. As the poem circulated globally, the first American edition was published by Robert Bell in 1777. Bell’s two volumes selectively mined elements from earlier editions—grafting on Newton’s “Biography of Milton,” Andrew Marvel’s commendatory verses, and Milton’s statement on the poem’s blank verse. Bell’s edition also ended the first volume with Book XI, leaving the reader in suspense and needing to purchase the second volume in order to complete the work. Both volumes, however, are smaller octavos, and Bell, a Scottish immigrant, was known for printing affordable copies of notable works, including those by Benjamin Franklin, Samuel Johnson, Daniel Defoe, and Oliver Goldsmith. Bell’s most famous publication would be Common Sense, commissioned by Thomas Paine during the American Revolution. That Bell decided to print Paradise Lost by the anti-Royalist Milton in 1777 of all times in American history is quite telling of the poem’s political resonances.

These early editions of Paradise Lost reveal how Milton’s name extended further with each successive edition—penetrating into the circles of the educated, the scholarly, the wealthy, the powerful elite, the nobility, and even the everyday reader from within and later beyond England—with tremendous assistance from his printers and booksellers.

References

Depledge, Emma, John S. Garrison, and Marissa Nicosia. Making Milton: Print, Authorship, Afterlives, 2021. Print.

Fulton, Thomas. Historical Milton: Manuscript, Print, and Political Culture in Revolutionary England. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press, 2011. Print.

Milton, John. The Poetical Works of John Milton: Ed., with Memoir, Introductions, Notes and an Essay on Milton’s English and Versification. New York: Macmillan Co, 1903. Print.

Shawcross, John T. Milton: A Bibliography for the Years 1624-1700. Binghamton: SUNY Binghamton, 1984. Print.

by

by