When I was eight years old, I spent hours combing through a clover patch in my parents’ backyard, searching determinedly for an elusive specimen: the four-leafed clover. At length, persistence paid off, and when I ran inside, it was with a lucky clover clasped in my hand. My mother told me that the best way to preserve my find was to press it between the pages of a book and let it dry, so I immediately set off in search of the biggest, heaviest tome in my bookcase. I shut the four-leafed clover firmly in the middle of my children’s illustrated bible before moving on to whatever business next consumed me. Book and clover both were soon after donated to a library book sale, and I never got to see the result of this early attempt at botanical preservation.

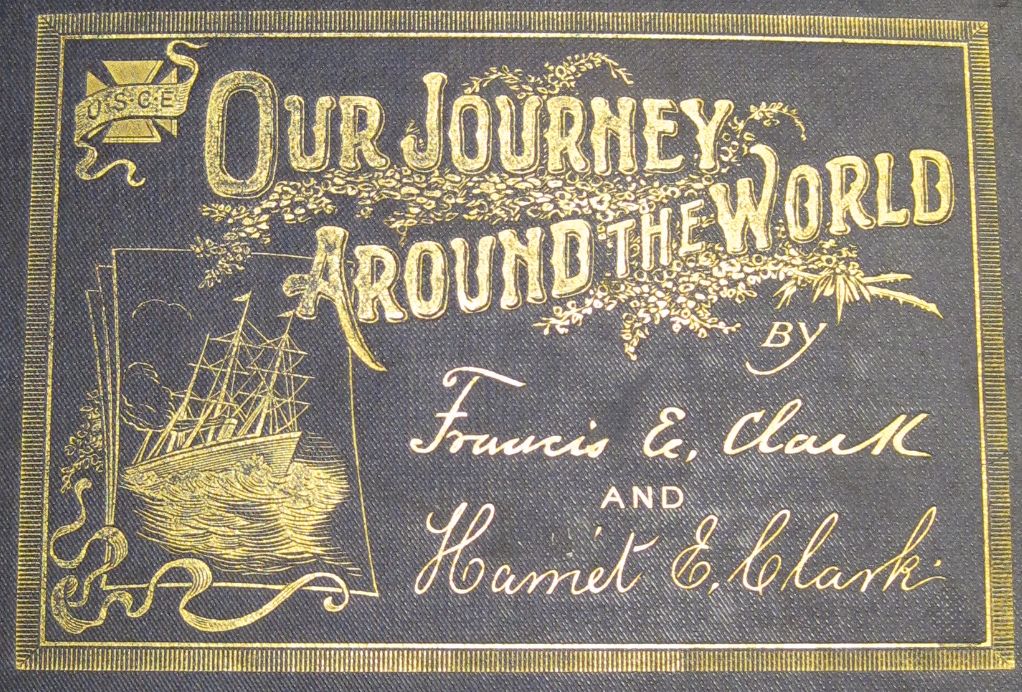

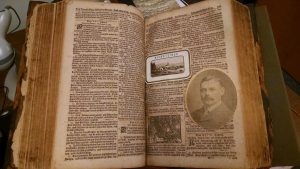

After my initial disappointment over losing the clover had passed, I began to imagine some other child flipping through the bible and serendipitously finding my treasure. Working in, borrowing from, and generally frequenting a number of libraries, I myself have made many such discoveries of ephemera, or, as defined by life-long ephemera-hunter Maurice Rickards in The Encyclopedia of Ephemera (yes, there’s a whole encyclopedia devoted to ephemera), “the minor transient documents of everyday life” (Rickards v). In books donated or returned, I’ve uncovered countless improvised bookmarks, from postcards and scrap paper to playbills and family photos. Each tells its own unique, often strange story within the story of the text. Not that the story is always easily deciphered — without a first-person explanation of the original reader’s intentions (which could very well have been nothing more than to mark his place with anything near to hand), we can often only speculate about ephemera’s significance. Sometimes – as with my strangest discovery to date, a pair of women’s underwear sandwiched in a chemistry textbook – its significance is not something I care to consider too deeply. Usually, however, uncovering a relic of past readership feels like a gift from the owner who laid some piece of herself, her time, or her culture into a book. Like annotations, bookplates, and ownership stamps, ephemera can be a reminder of the many human hands an old book has passed through, and give us insight (albeit sometimes fanciful) into how those men and women interacted with a single volume, each one making it their own.

A recent project to process and record the ephemera housed in SLU’s rare books has enabled me to acquaint myself with some of the strangest things in our books. As I processed each piece of ephemera, I began to think of our books not only as texts that can be studied for their intellectual content or as artifacts to be appreciated for their craftsmanship and artistic value, but also as presses, containers, and scrapbooks for preserving the assorted miscellania of life. Our collection, I found, is a veritable curiosity cabinet brimming with information in all media and from all periods. What follows is a mere taste of what I found.

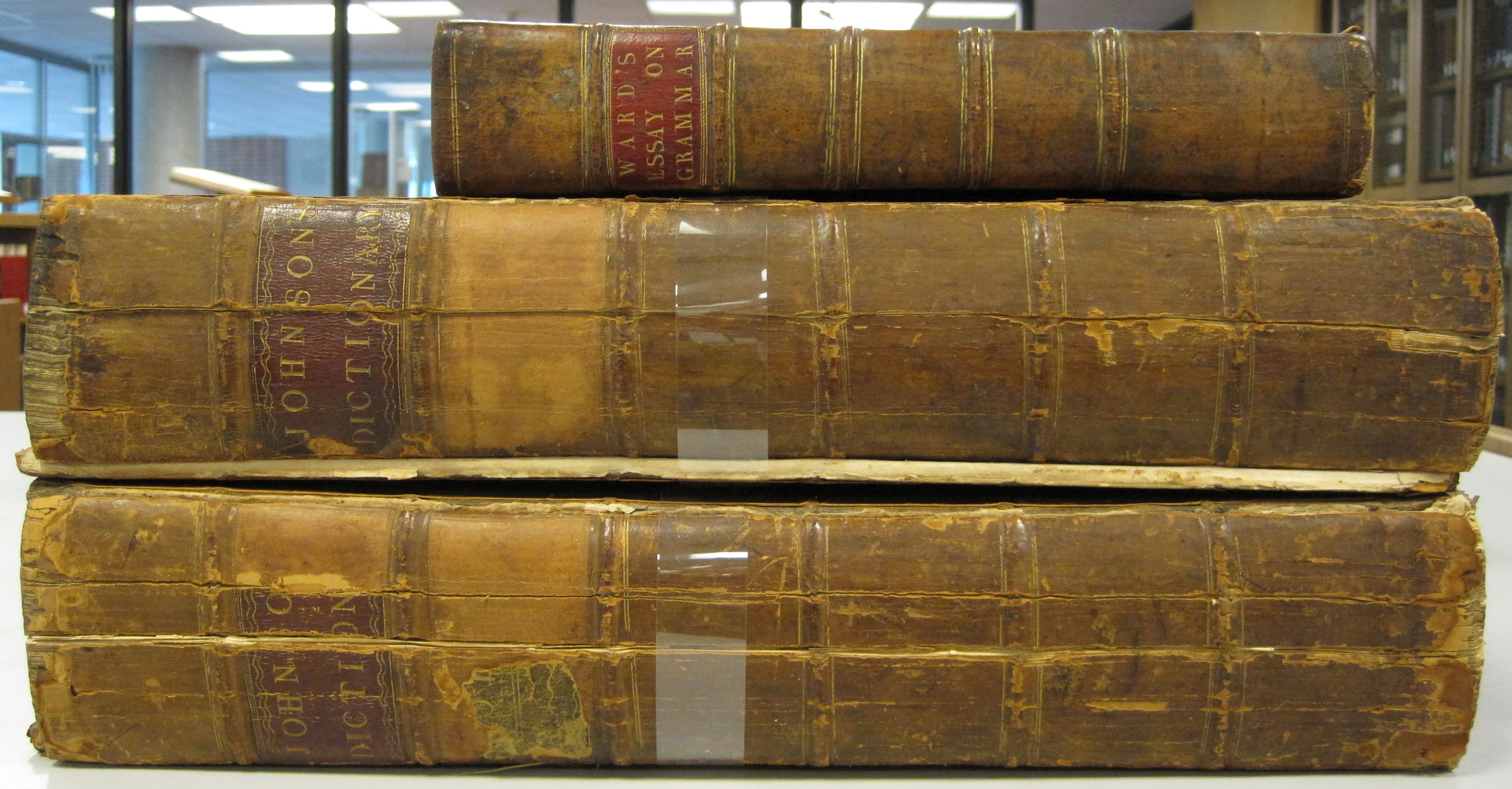

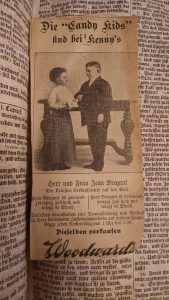

Among the printed ephemera tucked away in our pre-1820 collection is this early-twentieth-century newspaper clipping featuring a photograph of married couple Jean and Inez Bregant. The couple, a pair of little people whose claim to fame (according to this article) was that their adult heights were “seven and forty” and “two and forty” inches respectively, shared a colorful life. They met as vaudeville performers on Coney Island in 1904, opened their own grocery business in Council Bluffs, Iowa in 1912, and became (quite successful) demonstrators for John G. Woodward’s local candy company. This clipping appears to be an advertisement from their sales days, and is one of those rare (and rewarding) pieces of ephemera that serves as a clue to a traceable, documented story.

Another example of printed ephemera is this advertisement for Hall’s Corn Cure. (Remember how Capulet goads his young female guests into dancing during the fateful opening ball of Romeo and Juliet, taunting, “she that makes dainty, she, I’ll swear, hath corns” [Romeo and Juliet, Act I, Scene V]? Well, in twenty-first century translation, a corn is a painful beast of a callous.) The small brochure, distributed by druggist H.H. Ink of Canton, OH, not only provides an amusing glimpse into past advertising practices (it comprises mainly dramatic testimonials by clients who wax poetic on this miracle cure), but also provides us with a sense of place in the quest to learn more about the book’s past owners.

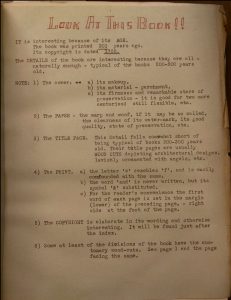

One of my favorite pieces of printed ephemera, however, is this typewritten note to future readers. The author emphatically beckons to us to “LOOK AT THIS BOOK!!,” and outlines the features that, in his or her opinion, make the volume noteworthy. The letter was written in either 1929 or 1932, when the book was probably still in the main stacks at SLU, and, to me, represents the birth of a bibliophile in our library.

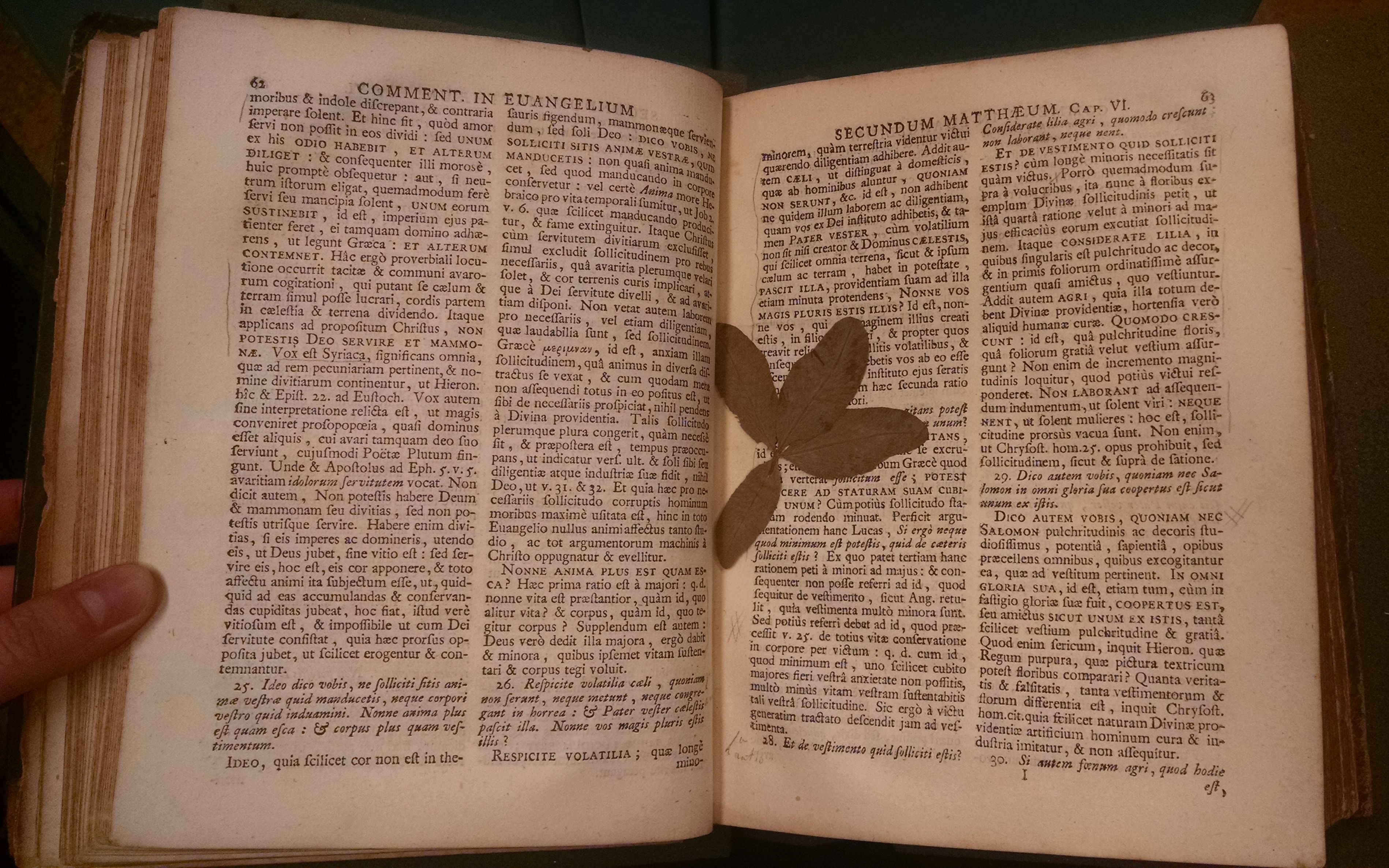

Standing in for the manuscript ephemera in our collection is a letter found in a book about heaven’s court. The writer celebrates celibacy, particularly for women, and includes the line, “Let the ungrateful world sneer at the maiden aunt, but God has a throne burnished for her arrival…” (Austen’s Miss Bates, finally vindicated!). Unlike the other ephemera listed here, this written meditation seems to be inspired by — and naturally connected to — the text.

Some of our most charming examples of ephemera are neither printed nor manuscript, and, in fact, carry no written information at all. Since ours is a predominantly paper collection, these alternative materials tend to stand out. One such example is a simple swatch of patterned fabric. As cloth goes, it is fairly unremarkable, but it retains its original deep-hued colors, and it speaks to me of the life of the reader who folded it into the book. This fabric is a standard cotton print, and I imagine that the bulk of the material was used to make a garment for everyday use. Because day-to-day needlework so often fell to the women of past centuries, I picture the previous owner who handled this swatch as a woman. Women’s stories so often go unspoken in the written record that any scrap of historical textile – the most lasting medium through which everyday women were able to express themselves – seems significant.

Even more evocative of women’s lives and work is this tiny sampler, tucked away in a text for safekeeping. Despite the aging of the fabric, which has browned over time, this small piece of work continues to demonstrate the skill and precision of the girl who began to sew it.

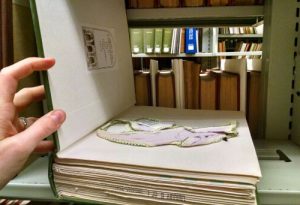

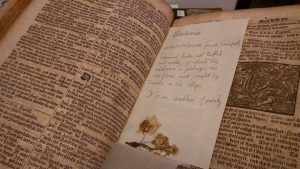

Finally, there are the pressed plants, including this delicate – but astonishingly still intact – bouquet of edelweiss (that snowy alpine flower lifted to fame by Christopher Plummer and co. in The Sound of Music). There are a number of pressed leaves hidden among the pages of our collection, their veins growing lacy with age, but this bouquet, accompanied by a handwritten note about its symbolism, is the most remarkable botanical specimen I’ve found. The care with which the flowers have been picked, bound together, documented, and preserved makes me feel truly connected to the reader who placed them here so tenderly, for I remember how the same impetus to preserve drove my eight-year-old self. Looking at these flowers — and all the other odds and ends of life stashed away in our books here at SLU — I feel glad that that long-ago clover passed prematurely from my hands. I can only hope that it sits patiently within its bible on a child’s bookshelf, waiting to become someone else’s adventitious (and perhaps even lucky) discovery.

by

by