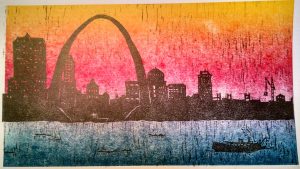

Autumn: “season of mists and mellow fruitfulness” – but also of crafts and harvest festivals. Growing up in New England, I placed fall festivities like Old Deerfield Craft Fair and the Eastern States Exposition right up there with Halloween on the list of Major Events of childhood importance. Now, transplanted to the Midwest, I both take comfort in the familiarity of local seasonal festivals and see them as a means to acquaint myself with the region through the distinct output of its creative community. At last month’s St. Louis Small Press Expo, for example, I came across a stunning print of the St. Louis skyline that speaks volumes about the city it depicts. In this image, produced by Westminster Press on Cherokee Street, we see a colorful, urban landscape, modern and undergoing constant improvement (see the construction equipment silhouetted on the right), but defined by its history. Here, references to the past are embodied not only by the symbolism of the Arch or the riverboat in the foreground, but by the artists’ choice of a traditional – and fascinating – form: the woodcut.

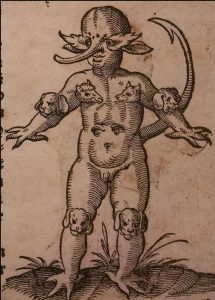

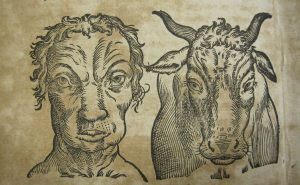

Woodcuts – prints made from designs carved along the grain of a block of wood – have been around for centuries, and are well-represented in SLU’s rare books collection. Woodcutting is the oldest method of relief printing, and – like paper-making, printing, and marbling – it originated in the East. The earliest known woodcut, depicting two Buddhist charms, was commissioned in Japan by Empress Shotoku sometime between A.D. 762 and 769, while the first woodcut-illustrated book, the Diamond Sutra, was produced in China in 868. It wasn’t until the fifteenth century – hand-in-hand with the adoption of Gutenberg’s moveable type – that woodcutting became common in Europe. There, the first woodcuts were printed not in books, but as broadsides catering to (somewhat contradictory) popular pastimes: pilgrimage and gambling. Devotional prints flooded the market (the survival of even some of these ephemeral documents attests to their popularity) and hand-colored decks of playing cards became available to wealthier customers. It was in 1460 that woodcuts made their European book debut in the workshop of printer Albrecht Pfister, the first German to send woodblocks through the press with movable type.

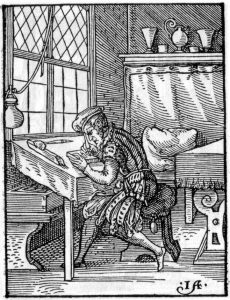

Early woodblocks were usually the creative work of two individuals: the artist who drew the design and the carver who transferred it to wood. In Germany, the craftsmen who produced woodblocks were called “Formschneiders,” (“cutters of forms”) and were classed with carpenters in the guild system. These craftsmen did not engage in original artistic expression, but accurately reproduced artists’ work in a widely distributable format, pre-copy machine. This role is made clear in Jost Amman’s 1568 book of trades, where the image (a woodcut) of a Formschneider at work is accompanied by verse that translates, “I cut so well with my knife every line on my blocks, that when they are printed… you see clearly the very lines that the artist has traced, his drawing whether it be coarse or fine reproduced exactly line for line.” This skilled partnership between artist and woodcutter facilitated the duplication and distribution of such great work as Albrecht Dürer’s, and it was only in the nineteenth century, with the rise of the Arts and Crafts Movement, that woodcutting became the work of one person rather than two.

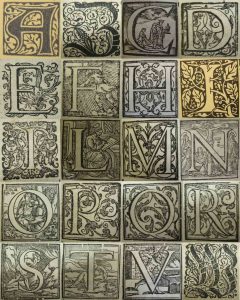

Woodblocks are resilient and take considerable time and skill to craft, so historically, a block was used until it no longer printed a clean image. French woodcutter Papillon used a cut of the Virgin Mary carved in pear wood by his grandfather for ninety years at an estimated rate of 500-600 pulls per year, and only at the end of its life did he note that “the wood looked a little worn” (Bliss 7). Ornamental woodcuts with generalized designs, including decorative initials, printer’s devices, headpieces, and tailpieces, were reused by and even circulated among printers for decades, with the result that their designs don’t always logically complement the text. (Pagan gods, for example, might adorn the initials of a Christian text.) Some thrifty printers even “edited” old woodblocks through a process called “plugging.” The carver would bore a hole through the offensive section of the woodblock, drive in a plug of fresh wood, sand down the surface, and re-carve the newly blank slate. This practice had mixed, often amusing results, as in a 1494 edition of Launcelot du Lac in which a knight wearing a bishop’s mitre was re-carved wearing a crown, but with the pendants of his old hat still hanging down over his shoulders (Bliss 4).

While woodcuts are still used today, they gradually fell out of common use in the eighteenth century as a new form of illustration, wood-engraving, rose in popularity. Wood-engravings, made with gravers rather than knives and carved into the end grain of a piece of wood (a horizontal rather than a vertical section of a tree’s trunk), could be produced more efficiently than woodcuts. The new form enabled artists to instill full-blown illustrations with more sophisticated detail and subtlety of design, and woodcuts were, for the most part, relegated to the sole role of ornamentation.

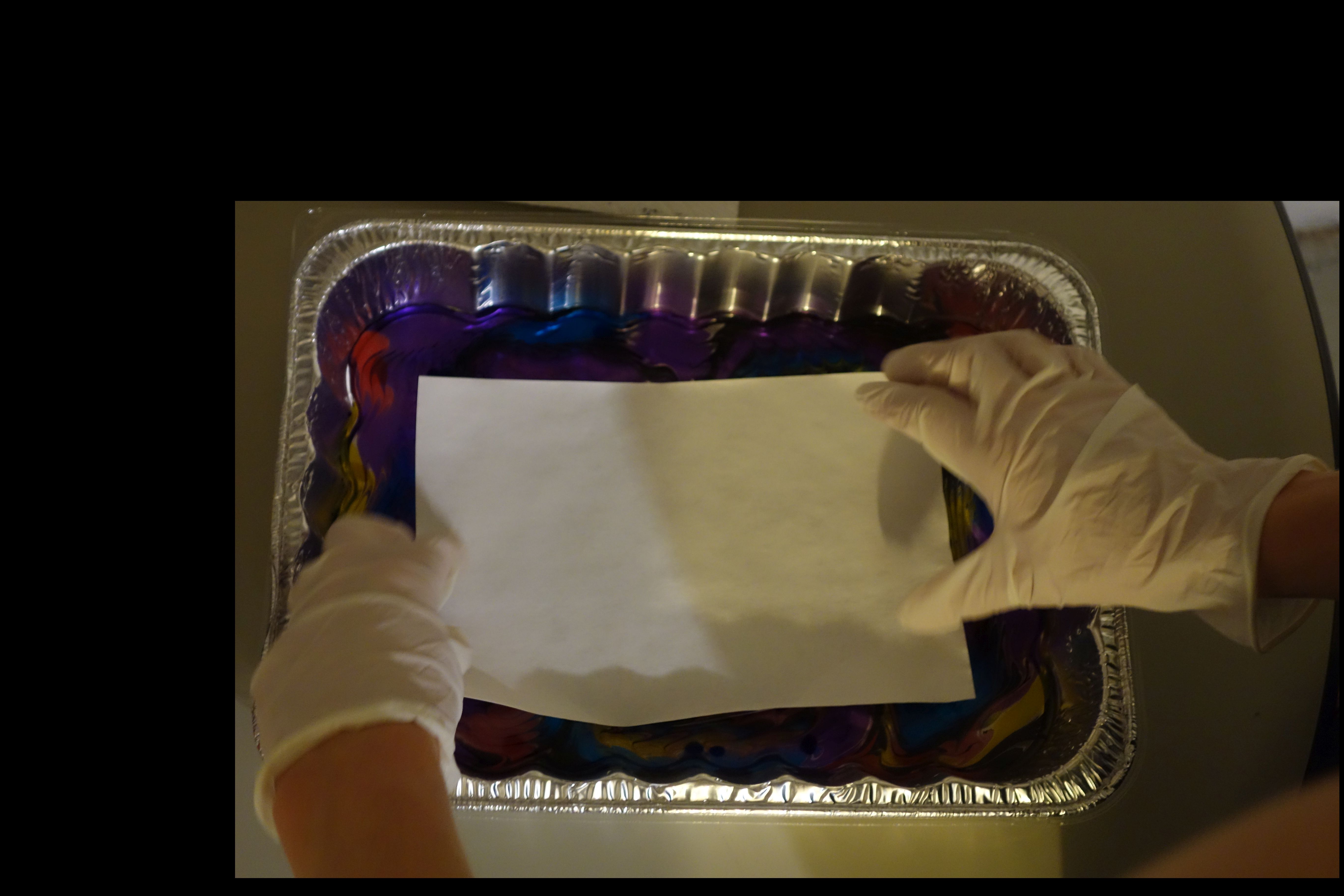

Today, a variety of materials are available for making prints stylistically similar to early woodcuts. Many vendors offer beginning print-making kits containing the necessary cutting tools (at minimum, a sharp knife and a scrive – a v-shaped tool used to cut a channel in a single stroke), ink, a roller to apply the ink, and a piece of the material into which you will carve your design. Some artists still use blocks of wood, as evidenced by the Westminster Press print pictured above. Linoleum, a softer, more malleable (and thus more forgiving) option, is also widely available. You can purchase plain sheets of linoleum cheaply at your local hardware store, but can also find sections cut to size and pre-mounted on wood blocks at most art supply stores. (Rip up your floor tiles, folks – it’s time to make some art!) Since linoleum is easier to cut than wood, it’s the better option for beginners, and, according to wood-engraver John R. Biggs, offers more “freedom of line” (Biggs 38).

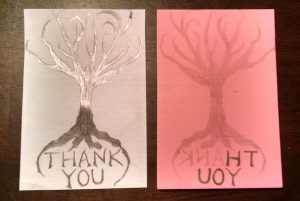

Short of the apples and potatoes you used in kindergarten, however, the least intimidating medium for a novice printmaker is rubber. This is the material I turned to in making my first print (baby steps, people). Rubber offers a soft, springy surface, freeing you to become acquainted with your tools (the same set of tools you will use to cut linoleum or wood) before facing off with a more obstinate canvas for your design. The printmaking process is relatively simple (albeit time consuming): you sketch a design on paper, transfer it to the surface you plan to carve, and cut away the background surrounding the design you want to print. (You can also sketch your design directly on the surface of your block, but this is trickier, as the sketch must be a mirror image of the desired print.) Then, you apply ink to your design with a roller and either lay a piece of paper over the inked block, burnishing it evenly, or flip the block over and press the inked side into a piece of paper. And voilà! You’ve made a print in relief.

… Now all you have to do is sign up for a booth at next fall’s craft fair.

by

by